“Addiction”, in the broadest of terms, is what social do-gooders call some people’s propensity to keep using drugs (including alcohol) in a way that is costing them a lot, and/or causing troubles, and/or is generally outside of cultural norms for substance use.

The popular explanation pushed by these do-gooders is that this “addiction” is a state of compulsion, in which the drug user is involuntarily using drugs. They are compelled by something – anything really – as long as the explanation holds to the idea that the “addicts” aren’t choosing their drug use freely. Many potential “causes” of this addiction have been and will continue to be posited, such as poor impulse control, an addictive quality inherent in drugs, social disconnection, underlying mental illnesses, childhood trauma, a flood of cheap drugs on the market, genetic weaknesses, and of course a disease of the brain.

I completely reject this view, and will now present my view: what we call addiction is a fully volitional pattern of behavior based on learned preferences, and often complicated by addiction mythology.

People use drugs because they want to. They want to, because of the benefits they see in drugs – fun, pleasure, relief, lowered inhibitions, etc. They can see many benefits in drugs that may or may not be there – regardless, it is their own view of these benefits, as well as their view of the benefits of their other options, that determines their want of drugs – their desire, urges, or craving for drugs. Or, in far less words: people use drugs because they like to.

They like using drugs more than they like not using drugs; they like using drugs often more than they like using them less often. They like being intoxicated more than they like being sober. And we could say this a million different ways depending on the person – Johnny likes getting high better than he likes doing his homework; Jane likes getting drunk better than she likes taking the kids to their games; Bill likes doing cocaine with strippers more than he likes paying his mortgage; etc. People who use drugs in troubling ways prefer to do so. You can describe this from a negative angle – Susan feels uncomfortable in her skin when she’s sober – but that’s another way of saying she feels more comfortable drunk, i.e. she prefers being drunk.

I don’t want to get too sidetracked here, but I’m going to pause to make a note: this doesn’t mean they want or like the bad things that can come along with heavy substance use, such as diseases, destroyed relationships, legal troubles, etc. It doesn’t mean they want to cause pain. It doesn’t mean they are evil or immoral. It just means that given how they see their alternatives, they are willing to pay this price to use substances. It is possible to recognize that they are choosing what they are doing, and still have sympathy for them, given the fact that this is unfortunately how they’ve come to see their options, and that they may have low self-esteem issues or a “broken spirit” so to speak – for whatever reasons – that contributes to their perspective that some highly destructive pattern of substance use is the best that they can do. Their problem doesn’t have to be a disease or compulsion for us to have compassion for their situation. I’m done digressing here though, I could write volumes, but this paragraph is for those who are ready to say that this is an unsympathetic view. I promise it is not. I once preferred drugs in this way, and it cost me a lot personally. The most compassionate thing that was done for me, was when someone stopped making excuses for me, put it to me straight, and showed me I was capable of seeing it differently and improving my choices.

That “addicts” often appear and/or feel “stuck” making the same choices even when they end up disliking much about their drug use isn’t all that odd. There are people who absolutely hate their jobs, and could technically get different jobs – yet they don’t. They appear stuck to some. They sometimes feel stuck themselves, and will emphatically proclaim that they have to stay at this job and have no other options. Yet they aren’t technically stuck, and this situation almost perfectly mirrors drug addiction. They see the job they hate as their best option. They either don’t think anyone else will hire them; don’t think it’s worth a minor pay cut to get a more enjoyable job; like the low expectations of their current job and are afraid of having a new boss; they don’t want to make a move or longer commute for a different job; etc. However it all works out in the calculus of their view of available options, they feel stuck in their current dead end job – but the reality is that they prefer it over the alternatives. The same can be said of romantic relationships – I’ve used both these analogies often. The problematic drug user simply has a strong preference for drug use; he isn’t “addicted” in the popular sense of using substances involuntarily. He is always free to choose to use drugs or not.

The twofold problem of addiction

“Addicts” are just people who have a strong preference for drug use. They can change this preference, and most do eventually (9 out of 10 will, in their lifetime, even though less than 1 in 4 will receive treatment). Most people diagnosed as addicts “mature out” of addiction in their 20s or 30s, and most do this without professional help. They develop new life roles, new interests, and generally tire of heavy drug use, becoming more interested in devoting their time and energy into other things. That is to say, they cease to prefer it as strongly as they once did – they begin to prefer life with less or no drug use. This isn’t a process of treating, curing, fighting, or recovering from an addiction – it is a process of changing a preference. However, this very natural process of change can be blocked and complicated – arrested and dragged out, when people are taught that “recovering from addiction” is a lifelong battle.

Most “addicts” don’t ever feel addicted. That is to say, most don’t feel like they’re doing something they don’t want to do. As long as they see their preference for intoxication as their own desire based on their own views, change will be easy and natural, when they see that they’d be better off with less drug use. But if they somehow learn to see themselves as “addicted,” all bets are off, and change becomes a struggle. This is when they begin to feel like they are doing something they don’t want to do. Their preference for drug use gets re-interpreted as something foreign to them; something separate from their own hierarchy of wants; an outside force that needs to be controlled, battled, treated, resisted, et cetera.

So “addiction” then, is a twofold problem. The first part of the problem is that we prefer an activity that is becoming very costly, yet this part is simple. When WE SEE that our style of drug use costing more than it seems to be worth, we naturally look for a better option, some adjusted level of drug use and other use of our energy, and we naturally gravitate toward that option. If you suspect it’s no longer worth it, then change is simply a matter of asking yourself what would work better for you. This is an easy question to answer, and being sure of your answer, follow-through is also simple, and basically effortless. Change, from this perspective, isn’t a matter of battling to resist an ongoing want (or urges or cravings), it’s a matter of pursuing the more attractive, and thus more preferred option. But the second part of the problem is that seeing yourself as addicted prevents you from implementing this simple solution of choosing differently; this addict identity leaves you fighting desire rather than changing it.

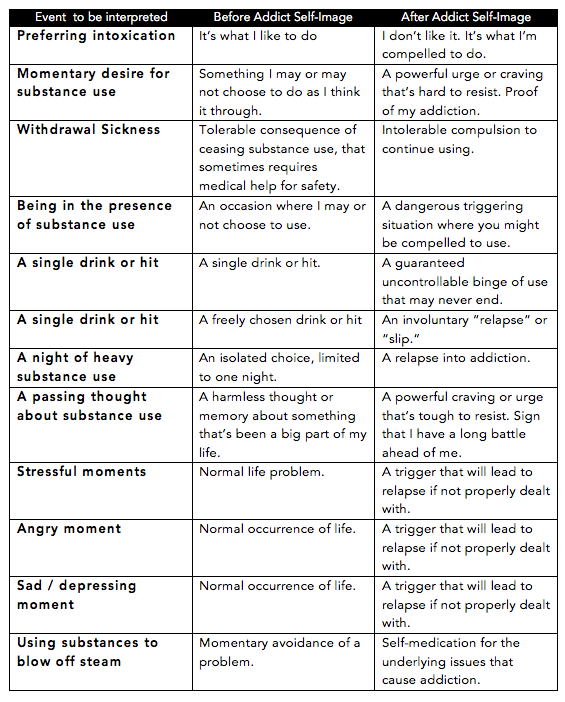

Once you view your desire for drugs as an addiction, and thus see things through the lens of addiction mythology, it affects the way you experience numerous things, creating a whole slew of unnecessary difficulties and battles. This chart I made for The Freedom Model for Addictions: Escape the Treatment and Recovery Trap (which is also used at The Freedom Model Retreats) describes some of the ways things get distorted once we take on the identity of “addict”:

In other words, once we start to think of ourselves as “addicts” we psych ourselves out of easily changing. Everything becomes a battle. We become fragile – “triggered” by anything and everything. And most of all, we become distracted from simply figuring out what adjustment we could make to our substance use that would simply make us happier.

Yes, that’s right – fighting addiction stops you from changing. The reason is that you’re now fighting a non-existent thing, a boogieman. There is no foreign thing called an addiction that pushes you to want and to use drugs. There is just your own point of view on drugs that pushes you to want and to choose to use them. the only thing that will change your desire is the act of developing a new preference – that is, changing your perspective on your options, and coming to see some different level of use as truly more rewarding. Or, more plainly, making a new choice, the choice to look at your options differently.

Yet, you’re hung up on trying to resist your want. And so what do you do? Sit there focused on what should deter you from using. That is, you focus on the risks, costs, or downsides of your preferred activity of using alcohol or other drugs. And this doesn’t necessarily make less drug use look more preferable. You have known the costs of heavy substance use for a long time, and have already shown that you’re willing to pay that price. Why should focusing on the costs all of a sudden deter you at this point, if they haven’t deterred you up to now? They usually won’t, or if they do, the deterrence is usually short lived. You go back to heavy drug use for the same reasons you did it to begin with – because despite what it costs, it appears to be the most beneficial option you have available.

I can’t say this enough: trying to quit based on avoidance of costs, risks, or out of “shoulds” or thoughts like “I have to quit,” or out of shame is not effective. Here’s why:

If we do something stimulated solely by the urge to avoid shame, we will generally end up detesting it.

-Marshall Rosenberg, Nonviolent Communication

We end up hating quitting because we failed to develop any positive reasons to do it. It’s just a chore to us. I hate chores. Most people do. I hate “duty” – the very term oozes “obligation.” I hate shame – it makes me feel bad! These aren’t recipes for positive goal commitment.

These negative quit attempts often become a cycle of temporarily stopping or cutting down, and then returning to the same problematic level of use, leaving you feeling like more of a failure, and more stuck & addicted each time. The missing element is a positive vision, a new perspective where some modified level of use is seen as more rewarding. You won’t find this perspective while you’re simply trying to resist, and to deter yourself.

The twofold solution to addiction

Drug use is a positive choice. That is to say, it is a choice made in the pursuit of happiness. We have reasons we prefer and choose drug use – we see benefits in it. If you can see greater benefits in modifying your drug use, you will move on quickly and easily to that modified level of use (modified includes any number of conceptions of moderation, and abstinence). Pay attention to this: Knowing that it is a very costly behavior isn’t enough to make you change. People freely choose to pay a high price for many things they want in life every day, when there are much cheaper options clearly available. Do you need cable tv? Hell no. Is it expensive? Hell yes. Does that stop most homes from having it? No, it clearly doesn’t. Nor does an average cost of a quarter million dollars stop people from deciding to raise children. Nor does the existence of cheap bare-bones apartments stop people from choosing to buy luxury homes. Likewise, the fact that the option of abstinence lacks all of the costs of drug use, doesn’t stop people from using drugs. We get cable tv for the benefits we see in it, we raise kids for the benefits we see in it, and we buy luxury homes for the benefits we see in them – we do all of these things despite the high costs and the existence of far cheaper alternatives. These are all positive choices – that is, they are made in the pursuit of happiness.

There are plenty of troubling choices with costly tradeoffs that are nonetheless made in the pursuit of happiness. This quote from french philosopher Blaise Pascal sums it up well:

“All men seek happiness. This is without exception. Whatever different means they employ, they all tend to this end. The cause of some going to war, and of others avoiding it, is the same desire in both, attended with different views. The will never takes the least step but to this object. This is the motive of every action of every man, even of those who hang themselves.”

Don’t get hung up on the fact that drug use is a messy choice. There are plenty of behaviors we all recognize as free choices that are messy too. This is a natural struggle of being human. As long as you see your preference for drug use as a special problem called an “addiction”, then you won’t be approaching it in the right way. All of the mythology about addiction stands in the way of simply and directly choosing to change. So if you believe you are addicted, the best thing you can do is to rid yourself of this addiction & recovery mythology first – and get back to seeing yourself as doing what you want to do, being in control of yourself, and making your own choices.

The first challenge and part of the solution is to learn this: nothing outside of you causes you to use drugs, nor does a disease or weakness inside of you cause you to choose drugs – it is a positive choice you make like any other, in the pursuit of happiness. We’ll call this part of the solution “escaping the addict identity.”

The second challenge and part of the solution is to reexamine the benefits of your preferred level of substance use, and to reexamine the benefits of some modified level of substance use. We’ll call this “the positive choice process.”

Part 2 isn’t always easy, but it’s simple. It doesn’t require strength, support, treatment, or the eradication of any “underlying causes of addiction” or avoidance of “triggers” etc – because those are all artifacts of addiction mythology. Part 2 just requires that you get beyond the addiction mythology, and have the willingness to look for better options, and try looking at your options differently than you have in the past. If you find that modified use is truly more appealing and preferable, change is then easy. If you don’t, then you can either seek out more information and perspectives on your options, or you can settle your mind that your current level of drug use is your best option, and stop beating yourself up over it. If upon further examination, it really is the thing you need to do to be happy, then there should be no further shame in it. It’s your life and your happiness, and you should do with it what seems best from your own judgment. Nobody could have a better handle on what will make you happy than you yourself.

Escaping the Addict Identity

Addiction mythology is taught to us from a young age, so even if you’ve never been to a treatment program or addiction support group, you’ve been exposed to it. All the self-doubt that you have about your ability to change comes from addiction & recovery mythology, and the addict identity it promotes. This website is mainly devoted to debunking this mythology, so that readers can return to a state of seeing their drug use preference as the product of their own thinking. It is designed to show people they don’t have to identify as addicts.

So, when people say to me “All you do is criticize, but where’s your solution?” I’m a little taken aback, because a major part of my solution is to understand that you aren’t in fact addicted – that you have full power of choice over your substance use, and the beliefs that fuel your desire for drugs. The main reason you feel like you can’t stop is because you’ve been taught that you can’t stop. There are countless facets of addiction mythology to be combatted, but some of the most important issues, as I see it, are that:

- There is no disease of addiction

- There is no such thing as loss of control / involuntary drug use

- Withdrawal is a side issue and doesn’t cause involuntary drug use

- There is no special support or treatment needed to choose to change a substance use habit/preference

- Your current substance use preference is by no means a permanent thing – that is, it’s not a “chronic” disease you’ll deal with forever. Your preferences are fluid, changing with experience, new information, new ideas, and awareness of new options.

- “Cravings” aren’t something you “get” or that “happen to you” – but rather an active thing you do by ideating about the benefits of drugs. You don’t “get cravings” – you crave. There is an important difference.

Anyone or thing that helps you to see these truths is helpful. That is, learning these things is at least half (or more) of the solution to a drug use problem. Once you stop approaching your drug use preference as an addiction, you become free to approach it as a true matter of positive choice. That is, becoming critical of oppressive addiction mythology and rejecting it, is the key thing you can do to stop feeling addicted. You would never have felt addicted in the first place if you didn’t learn the addiction mythology.

The Positive Choice Process

Once you stop seeing yourself as addicted, then you can look at your desire for substances for what it truly is: a preference for a costly activity. So you get to work at re-assessing whether it’s your most beneficial option. You can start by critically analyzing what you get out of drugs.

- The relief – does it really relieve the emotional pains you might’ve thought it relieved in the past?

- The excitement – is it still as exciting as it used to be, or have you done it enough now that it might be getting boring?

- The pleasure – is it really as pleasurable as you thought it was before – or does it just provide a tingly feeling?

- The social benefits – is it really necessary as a social lubricant or disinhibitor – or can you be fine without it? Is it possible those are just placebo effects? (they are!)

And there are more aspects of the perceived benefits of drug use that can be critically assessed. If you shorten the list of benefits, this can change your preference for drug use.

Then you can critically analyze the benefits of modified drug use (including both moderation & abstinence).

- What do you stand to gain in the following areas if you reduce your substance use?:

- time

- money

- independence

- new opportunities

- new pleasure and excitement in other things

As you look at modified use in these terms of benefits, then a modification of your use may genuinely begin to look more preferable to you than your current level of use. Again, the new element here has to be that your main focus is on the benefits of your various options rather than on the costs. We’ll pay anything for something we think we absolutely need and/or is our only good choice. Most people who feel like they must use drugs at high levels see lower levels of substance use as intolerable and a punishment. To happily and easily change, you must find a way to see modified use or abstinence as truly more rewarding than heavy use. Sometimes this takes some serious thought and soul-searching, depending on how beat down you are in spirit.

I can’t stress this enough though – once people know they aren’t addicted, it usually ends up being very easy and natural for them to find some change in use as more rewarding and preferable. This positive choice process happens almost naturally, since we are all constantly looking for greater happiness in life.

There you have it

All of the debunking of addiction mythology on this website is, in a sense, a solution. People want treatments, “tools”, techniques, medications, support systems, etc – they want big tangible solutions where something is done to the “addict” in some way, or the “addict” is given a clever process of some sort. No such thing is needed, and would be a further distraction from a real solution to heavy drug use. The solution is for you, the individual drug user, to figure out what level of drug use makes you happiest from your own judgment – and when you really know what that is, pursuing it requires no special strength. You don’t need people to “support” you – cheering you on to be abstinent or use moderately when these are things that you really want. So one of the top ways that I believe that I can help other people to do this is to clear away the confusing addiction mythology that convinces them to treat this as something other than a choice. Any feeling of being powerless or addicted is just a product of addiction & recovery mythology.

There you have it. This is my vision of the solution to “addiction.” People are always asking me for it, and I’ve said it implicitly all over the site, I’ve also said it much briefer in some places around this site too – but I thought I should have one page where I say it very clearly. It amounts to learning that you aren’t really addicted (nobody is) – you’ve just learned to interpret your preference as an addiction – and learning that you have full power to choose; and learning that the choice to change is a positive choice, rather than a negative choice. If you choose to simply resist your desire without reexamining what fuels it, then it will feel like a struggle, because your desire will be left intact. If you look for the happier option, and find it in modified use, it will be easy to follow through on, your desire will be changed.

Nobody is addicted, and thus nobody needs to recover. If people have a troubling preference for substance use, then they can change it by choosing to try a different level of substance use that may work better for them. It is a choice, plain and simple. Coming out of the fog of the addict identity, and realizing this, is one of the most liberating and exciting experiences I have ever had. I hope you have it too.

I know this page page leaves many questions unanswered, many nuances unexplained. If you are still confused and want to clear up your confusion so you can become an informed and empowered decision maker in regards to substance use and “addiction” I suggest you get my book The Freedom Model for Addictions: Escape the Treatment and Recovery Trap. I wrote it with Mark Scheeren, who co-founded the Saint Jude Retreats in 1992 and has been teaching a non-12-step, non-disease based way to overcome substance use problems for almost 30 years, and Michelle Dunbar, who’s been in the same organization for 20 years. These folks have incredible insights and experience in helping people with substance use problems. If you need to get away to a retreat environment to focus and learn, we offer that too, but the book will be enough for many people to get back on track.

A few notes

– People can still quit or reduce their use while believing they are an “addict” and believing that they have an “addiction.” It just so happens that that usually (not always) results in a painful change that’s hard to sustain. So I’m not saying it’s impossible to change your drug use while believing the mythology, but you should know that only a minority of people do it this way. 80-90% of people diagnosable as addicted do not get formal help; 96% of them say they “don’t think they need it”, which indicates that they probably don’t think of themselves as truly “addicted” (involuntarily using); and yet more than 90% of people get over their “addictions” anyway. So again, it’s only a handful of people who fully buy into the idea of being addicted and get over their problems with this belief system. Research also indicates that beliefe in the disease model of addiction increases the odds of “relapse.”

– Withdrawal syndrome may require professional medical help. Yet it still doesn’t compel people to use drugs.

– There are many nuances to my views and to to communicating them. I wrote this brief 4000 word overview in a few hours, but I have also been in the process of finishing a book that will be a few hundred pages and has taken a few years to write. I’m finding it hard to communicate all the intricacies of this perspective on addiction in a few hundred pages – which means it’s even harder in a few thousand words.

– Even many people who say “I don’t believe addiction is a disease” are knee deep in addiction mythology and don’t even realize it. For example, if you are seeking treatment for addiction, then you are under the cloud of addiction mythology. You think someone needs to work some magic on you to make you quit. That doesn’t need to happen – you just need to find a way to truly see a modified level of substance use as more preferable in order to successfully implement it.

– I will edit, modify, and update this page as I see fit, without notation. Always improving it for clarity when I can.