They’re screaming it from the rooftops: “addiction is a disease, and you can’t stop it without medical treatment”! But why are they screaming it so loud, why are they browbeating us about it, why is it always mentioned with a qualifier? You don’t hear people constantly referring to cancer as “the disease of cancer” – it’s just “cancer”, because it’s obvious that cancer is a disease, it’s been conclusively proven that the symptoms of cancer can’t be directly stopped with mere choices – therefore no qualifier is needed. On the other hand, addiction to drugs and alcohol is not obviously a disease, and to call it such we must either overlook the major gaps in the disease argument, or we must completely redefine the term “disease.” Here we will analyze a few key points and show that what we call addiction doesn’t pass muster as a real disease.

Real Diseases versus The Disease Concept or Theory of Drug Addiction

In a true disease, some part of the body is in a state of abnormal physiological functioning, and this causes the undesirable symptoms. In the case of cancer, it would be mutated cells which we point to as evidence of a physiological abnormality, in diabetes we can point to low insulin production or cells which fail to use insulin properly as the physiological abnormality which create the harmful symptoms. If a person has either of these diseases, they cannot directly choose to stop their symptoms or directly choose to stop the abnormal physiological functioning which creates the symptoms. They can only choose to stop the physiological abnormality indirectly, by the application of medical treatment, and in the case of diabetes, dietetic measures may also indirectly halt the symptoms as well (but such measures are not a cure so much as a lifestyle adjustment necessitated by permanent physiological malfunction).

In addiction, there is no such physiological malfunction. The best physical evidence put forward by the disease proponents falls totally flat on the measure of representing a physiological malfunction. This evidence is the much touted brain scan[1]. The organization responsible for putting forth these brain scans, the National Institute on Drug Abuse and Addiction (NIDA), defines addiction in this way:

In addiction, there is no such physiological malfunction. The best physical evidence put forward by the disease proponents falls totally flat on the measure of representing a physiological malfunction. This evidence is the much touted brain scan[1]. The organization responsible for putting forth these brain scans, the National Institute on Drug Abuse and Addiction (NIDA), defines addiction in this way:

Addiction is defined as a chronic relapsing brain disease that is characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use, despite harmful consequences. It is considered a brain disease because drugs change the brain – they change it’s structure and how it works. These brain changes can be long lasting, and can lead to the harmful behaviors seen in people who abuse drugs.

The NIDA is stating outright that the reason addiction is considered a disease is because of the brain changes evidenced by the brain scans they show us, and that these changes cause the behavior known as addiction, which they characterize as “compulsive drug seeking and use”. There are three major ways in which this case for the disease model falls apart:

- the changes in the brain which they show us are not abnormal at all

- people change their behavior IN SPITE OF the fact that their brain has changed in response to repeated substance use jump to section

- there is no evidence that the behavior of addicts is compulsive (compulsive meaning involuntary) (point two addresses this, as well as some other research that will be presented) jump to section

This all applies equally to “alcoholism” as well. If you’re looking for information on alcoholism, the same theories and logic discussed here are applicable; wherever you see the term addiction used on this site, it includes alcoholism.

Brain Changes In Addicts Are Not Abnormal, and Do Not Prove The Brain Disease Theory

On the first count – the changes in the brain evidenced by brain scans of heavy substance users (“addicts”) do not represent a malfunctioning brain. They are quite normal, as research into neuroplasticity has shown us. Whenever we practice doing or thinking anything enough, the brain changes – different regions and neuronal pathways are grown or strengthened, and new connections are made; various areas of the brain become more or less active depending upon how much you use them, and this becomes the norm in your brain – but it changes again as you adjust how much you use those brain regions depending on what you choose to think and do. This is a process which continues throughout life, there is nothing abnormal about it. Here, Sharon Begley describes neuroplasticity: [2]

The term refers to the brain’s recently discovered ability to change its structure and function, in particular by expanding or strengthening circuits that are used and by shrinking or weakening those that are rarely engaged. In its short history, the science of neuroplasticity has mostly documented brain changes that reflect physical experience and input from the outside world.

So, when the NIDA’s Nora Volkow and others show us changes in the brain of a substance user as compared to a non-substance user, this difference is not as novel as they make it out to be. They are showing us routine neuroplastic changes which every healthily functioning person’s brain goes through naturally. The phenomenon of brain changes isn’t isolated to “addicts” or anyone else with a so-called brain disease – non-addicted and non-depressed and non-[insert brain disease of the week here] people experience neural adaptations too. One poignant example was found in the brains of London taxi drivers, as Begley and Jeffrey Schwartz pointed out in The Mind and The Brain. [4]

Is Being A Good Taxi Driver A Disease?

A specific area of the brain’s hippocampus is associated with creating directional memories and a mental map of the environment. A team of researchers scanned the brains of London taxi drivers and compared their brains to non-taxi drivers. There was a very noticeable difference, not only between the drivers and non-drivers, but also between the more experienced and less experienced drivers:

There it was: the more years a man had been a taxi driver, the smaller the front of his hippocampus and the larger the posterior. “Length of time spent as a taxi driver correlated positively with volume in…the right posterior hippocampus,” found the scientists. Acquiring navigational skills causes a “redistribution of gray matter in the hippocampus” as a driver’s mental map of London grows larger and more detailed with experience. [4]

So, the longer you drive a cab in London (that is, the longer you exert the mental and physical effort to quickly find your way around one of the world’s toughest to navigate cities), the more your brain physically changes. And the longer you use drugs, the more your brain changes. And indeed, the longer and more intensely you apply yourself to any skill, thought, or activity – the more it will change your brain, and the more visible will be the differences between your brain and that of someone who hasn’t been focused on that particular skill. So, if we follow the logic of the NIDA, then London’s taxi drivers have a disease, which we’ll call taxi-ism, that forces them to drive taxis. But the new diseases wouldn’t stop there.

Learning to play the piano well will change your brain – and if you were to compare brain scans of a piano player to a non-piano player, you would find significant differences. Does this mean that piano playing is a disease called Pianoism? Learning a new language changes your brain, are bilingual people diseased? Athletes’ brains will change as a result of intensive practice – is playing tennis a disease? Are soccer players unable to walk into a sporting goods store without kicking every ball in sight? We could go on and on with examples, but the point is this – when you practice something, you get better at doing it, because your brain changes physiologically – and this is a normal process. If someone dedicated a large portion of their life to seeking and using drugs, and their brain didn’t change – then that would be a true abnormality. Something would be seriously wrong with their brain.

Its not just physical activity that changes our brains, thoughts alone can have a huge effect. What’s more, whether the brain changes or not, there is much research which shows that the brain is slave to the mind. As Begley points out elsewhere, thoughts alone can create the same brain activity that would come about by doing things[2]:

Using the brain scan called functional magnetic resonance imaging, the scientists pinpointed regions that were active during compassion meditation. In almost every case, the enhanced activity was greater in the monks’ brains than the novices’. Activity in the left prefrontal cortex (the seat of positive emotions such as happiness) swamped activity in the right prefrontal (site of negative emotions and anxiety), something never before seen from purely mental activity. A sprawling circuit that switches on at the sight of suffering also showed greater activity in the monks. So did regions responsible for planned movement, as if the monks’ brains were itching to go to the aid of those in distress.

So by simply practicing thinking about compassion, these monks made lasting changes in their brain activity. Purely mental activity can change the brain in physiologically significant ways. And to back up this fact we look again to the work of Dr Jeffrey Schwartz[3], who has taught OCD patients techniques to think their way out of obsessive thoughts. After exercising these thought practices, research showed that the brains of OCD patients looked no different than the brains of those who’d never had OCD. If you change your thoughts, you change your brain physically – and this is voluntary. This is outside the realm of disease, this shows a brain which changes as a matter of normality, and can change again, depending on what we practice choosing to think. There is nothing abnormal about a changing brain, and the type of changes we’re discussing aren’t necessarily permanent, as they are characterized to be in the brain disease model of addiction.

These brain change don’t need to be brought on by exposure to chemicals. Thoughts alone, are enough to rewire the very circuits of the human brain responsible for reward and other positive emotions that substance use and other supposedly “addictive” behaviors (“process addictions” such as sex, gambling, and shopping, etc.) are connected with.

The Stolen Concept of Neuroplasticity in the Brain Disease Model of Addiction

Those who claim that addiction is a brain disease readily admit that the brain changes in evidence are arrived at through repeated choices to use substances and focus on using substances. In this way, they are saying the disease is a product of routine neuroplastic processes. Then they go on to claim that such brain changes either can’t be remedied, or can only be remedied by outside means (medical treatment). When we break this down and look at it step by step, we see that the brain disease model rests on an argument similar to the “stolen concept”. A stolen concept argument is one in which the argument denies a fact on which it simultaneously rests. For example, the philosophical assertion that “reality is unknowable” rests on, or presumes that the speaker could know a fact of reality, it presumes that one could know that reality is unknowable – which of course one couldn’t, if reality truly was unknowable – so the statement “reality is unknowable” invalidates itself. Likewise, the brain disease proponents are essentially saying “neuroplastic processes create a state called addiction which cannot be changed by thoughts and choices” – this however is to some degree self-invalidating, because it depends on neuroplasticity while seeking to invalidate it. If neuroplasticity is involved, and is a valid explanation for how to become addicted, then we can’t act is if the same process doesn’t exist when it’s time to focus on getting un-addicted. That is, if the brain can be changed into the addicted state by thoughts and choices, then it can be further changed or changed back by thoughts and choices. Conditions which can be remedied by freely chosen thoughts and behaviors, don’t fit into the general understanding of disease. Ultimately, if addiction is a disease, then it’s a disease so fundamentally different than any other that it should probably have a completely different name that doesn’t imply all the things contained in the term “disease” – such as the idea that the “will” of the afflicted is irrelevant to whether the condition continues.

People change their addictive behavior in spite of the fact that their brain is changed – and they do so without medication or surgery (added 4/18/14)

In the discussion above, we looked at some analogous cases of brain changes to see just how routine and normal (i.e. not a physiological malfunction) such changes are. Now we’re going to look directly at the most popular neuroscientific research which purports to prove that these brain changes actually cause “uncontrolled” substance use (“addiction”).

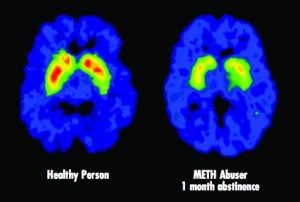

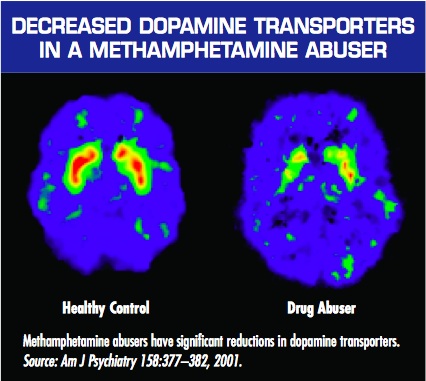

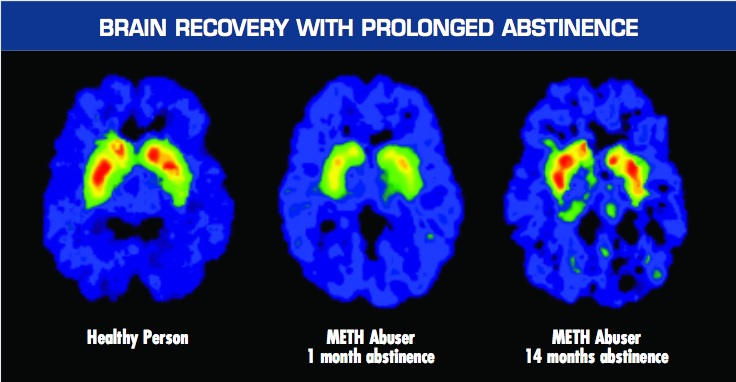

The most popular research is Nora Volkow’s brain scans of “meth addicts” presented by the NIDA. The logic is simple. We’re presented with the brain scan of a meth addict alongside the brain scan of a non-user, and we’re told that the decreased activity in the brain of the meth user (the lack of red in the “Drug Abuser” brain scan presented) is the cause of their “compulsive” methamphetamine use. Here’s how the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) explains the significance of these images in their booklet – Drugs, Brains, and Behavior: The Science of Addiction :

Just as we turn down the volume on a radio that is too loud, the brain adjusts to the overwhelming surges in dopamine (and other neurotransmitters) by producing less dopamine or by reducing the number of receptors that can receive signals. As a result, dopamine’s impact on the reward circuit of a drug abuser’s brain can become abnormally low, and the ability to experience any pleasure is reduced. This is why the abuser eventually feels flat, lifeless, and depressed, and is unable to enjoy things that previously brought them pleasure. Now, they need to take drugs just to try and bring their dopamine function back up to normal.

[emphasis added]

They go on that these same sorts of brain changes:

..may also lead to addiction, which can drive an abuser to seek out and take drugs compulsively. Drug addiction erodes a person’s self-control and ability to make sound decisions, while sending intense impulses to take drugs.

[emphasis added]

That image is shown when NIDA is vaguely explaining how brain changes are responsible for “addiction.” But later on, when they try to make a case for treating addiction as a brain disease, they show the following image, which tells a far different story if you understand more of the context than they choose to mention:

Again, this graphic is used to support the idea that we should treat addiction as a brain disease. However, the authors mistakenly let a big cat out of the bag with this one – because the brain wasn’t treated at all. Notice how the third image shows a brain in which the red level of activity has returned almost to normal after 14 months of abstinence. That’s wonderful – but it also means that the NIDA’s assertions that “Addiction means being unable to quit, even in the face of negative consequences”(LINK) and “It is considered a brain disease because drugs change the brain… These brain changes… can lead to the harmful behaviors seen in people who abuse drugs” are dead wrong.

When these studies were done, nobody was directly treating the brain of methamphetamine addicts. They were not giving them medication for it (there is no equivalent of methadone for speed users), and they weren’t sticking scalpels into the brains of these meth addicts, nor were they giving them shock treatment. So what did they do?

These methamphetamine addicts were court ordered into a treatment program (whose methodology wasn’t disclosed in the research) which likely consisted of a general mixture of group and individual counseling with 12-step meeting attendance. I can’t stress the significance of this enough: their brains were not medically treated. They talked to counselors. They faced a choice between jail and abstinence. They CHOSE abstinence (for at least 14 months!) – even while their brains had been changed in a way that we’re told robs them of the ability to choose to quit “even in the face of negative consequences.” [5]

Even with changed brains, people are capable of choosing to change their substance use habits. They choose to stop using drugs, and as the brain scans above demonstrate – their brain activity follows this choice. If the brain changes caused the substance using behavior, i.e. if it was the other way around, then a true medical intervention should have been needed – the brain would’ve needed to have changed first via external force (medicine or surgery) before abstinence was initiated. They literally wouldn’t have been able to stop for 14 months without a real physical/biological medical intervention. But they did…

Substance Use Is Not Compulsive, It Is A Choice

In his classic book Addiction & Opiates, Alfred R Lindesmith PhD explained the requirements of reliable scientific theories explaining the causes of things such as heroin addiction:

…a genuine theory that proposes to explain a given phenomenon by relating it to another phenomenon must, in the first place, have clear empirical implications which, if not fulfilled, negate the theory.

If the theory is that neural adaptations alone cause uncontrolled behavior, then this proposition can easily be shown to be false. I demonstrated above that in the midst of having fully “changed” or “addicted” brains, people do indeed stop using substances, so essentially, it is case closed. But the depths to which the brain disease theory of addiction can be negated go even further, because the basic theory of addiction as representing uncontrolled substance use has never been explained. Explanation of the mechanism by which substance use happens without the individual’s consent is conspicuously missing – yet such explanation is a necessary part of such a theory, as Lindesmith writes (again in Addiction & Opiates):

…besides identifying the two types of phenomenon that are allegedly interrelated, there must be a description of the processes or events that link them. In other words, besides affirming that something causes something else, it is necessary to indicate how the cause operates to produce the alleged effect.

“Here Comes the Bogey-Man” by Goya, circa 1799

There doesn’t seem to be any explanation or evidence that substance use is involuntary. In fact, the evidence, such as that presented above, shows the opposite. Nevertheless, when the case for the disease is presented, the idea that drug use is involuntary is taken for granted as true. No evidence is ever actually presented to support this premise, so there isn’t much to be knocked down here, except to make the point I made above – is a piano player fundamentally incapable of resisting playing the piano? They may love to play the piano, and want to do it often, they may even be obsessive about it, but it would be hard to say that at the sight of a piano they are involuntarily driven by their brain to push aside whatever else they need to do in order to play that piano.

There is another approach to the second claim though. We can look at the people who have subjectively claimed that their substance use is involuntary, and see if the offer of incentives results in changed behavior. Gene Heyman covered this in his landmark book, Addiction: A Disorder of Choice[3]. He recounts studies in which cocaine abusers were given traditional addiction counseling, and also offered vouchers which they could trade in for modest rewards such as movie tickets or sports equipment – if they proved through urine tests that they were abstaining from drug use. In the early stages of the study, 70% of those in the voucher program remained abstinent, while only 20% stayed abstinent in the control group which didn’t receive the incentive of the vouchers. This demonstrates that substance use is not in fact compulsive or involuntary, but that it is a matter of choice, because these “addicts” when presented with a clear and immediately rewarding alternative to substance use and incentive not to use, chose it. Furthermore, follow up studies showed that this led to long term changes. A full year after the program, the voucher group had double the success rate of those who received only counseling (80% to 40%, respectively). This ties back in to our first point that what you practice, you become good at. The cocaine abusers in the voucher group practiced replacing substance use with other activities, such as using the sports equipment or movie passes they gained as a direct consequence of abstaining from drug use – thus they made it a habit to find other ways of amusing themselves, this probably led to brain changes, and the new habits became the norm.

Long story short, there is no evidence presented to prove that substance use is compulsive. The only thing ever offered is subjective reports from drug users themselves that they “can’t stop”, and proclamations from treatment professionals that the behavior is compulsive due to brain changes. But if the promise of a ticket to the movies is enough to double the success rate of conventional addiction counseling, then it’s hard to say that substance users can’t control themselves. The reality is that they can control themselves, but they just happen to see substance use as the best option for happiness available to them at the times when they’re abusing substances. When they can see other options for happiness as more attractive (i.e. as promising a greater reward than substance use), attainable to them, and as taking an amount of effort they’re willing to expend – then they will absolutely choose those options instead of substance use, and will not struggle to “stay sober”, prevent relapse, practice self-control or self-regulation, or any other colloquialism for making a different choice. They will simply choose differently.

But wait… there’s more! (Added 4/21/14) Contrary to the claims that alcoholics and drug addicts literally lose control of their substance use, a great number of experiments have found that they are really in full control of themselves. Priming dose experiments have found that alcoholics are not triggered into uncontrollable craving after taking a drink. Here’s a link to the evidence and a deeper discussion of these findings: Do Addicts and Alcoholics Lose Control? Priming dose experiments of cocaine, crack, and methamphetamine users found that after being given a hit of their drug of choice (primed with a dose) they are capable of choosing a delayed reward rather than another hit of the drug.

Three Most Relevant Reasons Addiction Is Not A Disease

So to sum up, there are at least two significant reasons why the current brain disease theory of addiction is false.

- A disease involves physiological malfunction, the “proof” of brain changes shows no malfunction of the brain. These changes are indeed a normal part of how the brain works – not only in substance use, but in anything that we practice doing or thinking intensively. Brain changes occur as a matter of everyday life; the brain can be changed by the choice to think or behave differently; and the type of changes we’re talking about are not permanent.

- The very evidence used to demonstrate that addicts’ behavior is caused by brain changes also demonstrates that they change their behavior while their brain is changed, without a real medical intervention such as medication targeting the brain or surgical intervention in the brain – and that their brain changes back to normal AFTER they VOLITIONALLY change their behavior for a prolonged period of time

- Drug use in “addicts” is not compulsive. If it was truly compulsive, then offering a drug user tickets to the movies would not make a difference in whether they use or not – because this is an offer of a choice. Research shows that the offer of this choice leads to cessation of substance abuse. Furthermore, to clarify the point, if you offered a cancer patient movie tickets as a reward for ceasing to have a tumor – it would make no difference, it would not change his probability of recovery.

Addiction is NOT a disease, and it matters. This has huge implications for anyone struggling with a substance use habit.

References:

- 1) NIDA, Drugs Brains and Behavior: The Science of Addiction, sciofaddiction.pdf

- 2) Sharon Begley, Scans of Monks’ Brains Show Meditation Alters Structure, Functioning, Wall Street Journal, November 5, 2004; Page B1, http://psyphz.psych.wisc.edu/web/News/Meditation_Alters_Brain_WSJ_11-04.htm

- 3) Gene Heyman, Addiction: A Disorder of Choice, Harvard University Press, 2009

- 4) Sharon Begley and Jeffrey Schwartz, The Mind And The Brain, Harper Collins, 2002

- 5) Links to the 2 methamphetamine abuser studies by Nora Volkow:

http://www.jneurosci.org/cgi/content/full/21/23/9414

http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/reprint/158/3/377

Important Notes from the author to readers and especially commenters:

On “badness” or immorality:

Please do not attribute to me the idea that heavy substance users must be “bad” or “immoral” if they are in fact in control of and choosing their behavior. I do not think this. I think that at the time they’re using, it is what they prefer, given what life options they believe are available to them – and I don’t think it’s my job to decide what other people should prefer for themselves, and then declare them bad if they don’t live up to my vision of a “good” life. That’s what the disease recovery culture does, de facto, when they present the false dichotomy of ‘diseased or bad’. To say that addiction is chosen behavior is simply to make a statement about whether the behavior is within the control of the individual – it is not a judgment of the morality of the behavior or the individual choosing it.

On willpower:

Please do not attribute to me the suggestion to “use willpower.” I have not said that people should use willpower, nor do I think it’s a coherent or relevant concept in any way, nor do I think “addicts lack willpower” or that those who recover have more willpower, nor, and this is important, do I believe that a choice model of addiction necessarily implies willpower as the solution.

“Addicts” do not need extra willpower, strength, or support, to change their heavy substance use habits if that is what they want to do. They need to change their preference for heavy substance use, rather than trying to fight that preference with supposed “willpower.”

On compassion:

Please don’t accuse me of not having compassion for people who have substance use problems. You do not know that, and if you attack my motives in this way it just shows your own intellectual impotence and sleaze. I have a great deal of compassion for people with these problems – I was once one such person. I am trying to get at the truth of the nature of addiction, so that the most people can be helped in the most effective way possible. I don’t doubt the compassion of those who believe addiction is a disease, and I hope you’ll give me the same benefit of the doubt. I assure you I care and want the best for people – and I don’t need to see them as diseased to do so. When you see someone who’s gotten themselves into a mess, don’t you want to help, even if it’s of their own making? Why should we need to believe they have a disease to help them if the mess is substance use related? I don’t get that requirement.

Some Agreement I’ve Found From Addiction Researchers (added 6/10/14)

I began working out my understanding of the brain disease model back in 2005 as I started working on a book about addiction; published this article in 2010; and was happy to find in 2011 when I went back to work with Baldwin Research that they had arrived at a similar conclusion. The way they stated it amounted to “either everything is addiction, or nothing is” – referring to the fact that the brain changes presented as proof of addiction being a brain disease are so routine as to indicate that all behavior must be classified as addiction if we follow the logic.

I was also gratified to have found a neuroscientist who arrived at the same conclusions. I think Marc Lewis PhD and I may disagree on a few things, but it seems we may see eye to eye on the logic I presented above about such brain changes being routine, and thus not indicative of disease. Check what he wrote in 2012 for the PLOS Blog, Mind The Brain:

every experience that has potent emotional content changes the NAC and its uptake of dopamine. Yet we wouldn’t want to call the excitement you get from the love of your life, or your fifth visit to Paris, a disease. The NAC is highly plastic. It has to be, so that we can pursue different rewards as we develop, right through childhood to the rest of the lifespan. In fact, each highly rewarding experience builds its own network of synapses in and around the NAC, and that network sends a signal to the midbrain: I’m anticipating x, so send up some dopamine, right now! That’s the case with romantic love, Paris, and heroin. During and after each of these experiences, that network of synapses gets strengthened: so the “specialization” of dopamine uptake is further increased. London just doesn’t do it for you anymore. It’s got to be Paris. Pot, wine, music…they don’t turn your crank so much; but cocaine sure does. Physical changes in the brain are its only way to learn, to remember, and to develop. But we wouldn’t want to call learning a disease.

….

In my view, addiction (whether to drugs, food, gambling, or whatever) doesn’t fit a specific physiological category. Rather, I see addiction as an extreme form of normality, if one can say such a thing. Perhaps more precisely: an extreme form of learning. No doubt addiction is a frightening, often horrible, state to endure, whether in oneself or in one’s loved ones. But that doesn’t make it a disease.

I think that quote is very important, because it highlights neuronal changes that occur in the same region implicated in addiction (whereas the examples I presented earlier in the article represented some other regions).

In a brilliant paper titled “The naked empress: Modern neuro science and the concept of addiction”, Peter Cohen of The Centre for Drug Research at University of Amsterdam, states that:

The notions of addiction transformed into the language of neurology as performed by authors like Volkov, Berridge, Gessa or De Vries are completely tautological.

He essentially argues that Volkow et al take for granted that heavy drug and alcohol use is uncontrolled, identify neural correlates, and present them as evidence of uncontrollability. Yet they don’t do so with other behaviors, and he provides plenty of examples. He notes that they start with assumptions that certain patterns of behavior (e.g. heavy drug use) are uncontrolled, and others are controlled – based purely on cultural prejudices. He accurately identifies addiction as a learned behavior, or as routine bonding to a thing, and then expresses something very close to my thesis presented above (that all learned/intensely repeated behaviors result in “brain changes”).

The problem of course is that probably all learning produces temporary or lasting ‘change in neural systems’. Also, continuation of learned behavior may be functional in the eyes and experience of the person but less so in the eyes of the outsider. Who is right? We know of people remaining married in spite of-in the eyes of a beholder- a very bad marriage. Who speaks of lasting ‘neural change’ as the basis of the continued marriage? But, even when a person herself sees some behavior as counter functional, it is not necessarily seen as addiction. It may be seen as impotence, ingrained habit or unhappy adaptation. It all depends on which behavior we discuss, not on the brain.

The great points contained in this article would be done an injustice if I tried to sum them up here, so check it out for yourself at The Center for Drug Research University of Amsterdam. As with Marc Lewis, I suspect that Peter Cohen and I might have some substantial disagreements about the full nature of addiction and human behavior in general, but I think we at least agree that the changes in the brain of an “addict” do not necessarily represent disease, and more likely represent a routine process.

Writing in 2013 for the journal Frontiers In Psychiatry, esteemed behavioral and addiction researcher Gene Heyman pointed out something so painfully obvious that we don’t even take notice – no causal link has ever been found between the neural adaptations caused by excessive substance use and continued heavy use. That is, correlation is not causation:

With the exception of alcohol, addictive drugs produce their biological and psychological changes by binding to specific receptor sites throughout the body. As self-administered drug doses greatly exceed the circulating levels of their natural analogs, persistent heavy drug use leads to structural and functional changes in the nervous system. It is widely – if not universally – assumed that these neural adaptations play a causal role in addiction. In support of this interpretation brain imaging studies often reveal differences between the brains of addicts and comparison groups (e.g., Volkow et al., 1997; Martin-Soelch et al., 2001) However, these studies are cross-sectional and the results are correlations. There are no published studies that establish a causal link between drug-induced neural adaptations and compulsive drug use or even a correlation between drug-induced neural changes and an increase in preference for an addictive drug.

Did you get that? Let me repeat the words of this experienced researcher, PhD, and lecturer/professor from Boston College and Harvard who, in addition to publishing scores of papers in peer reviewed medical journals has also had an entire book debunking the disease model of addiction by Harvard University press (I say all of this about his credentials so that I can hopefully STOP getting commenters who say “but you’re not a doctor, and what are your credentials wah, wah, wah,……” here’s a “credentialed” expert who essentially agrees with most of what I’ve written in this article – so please, for the love of god, save your fallacious ad hominems and appeals to authority for another day!)- he (Gene Heyman PhD) said this, as of 2013:

There are no published studies that establish a causal link between drug-induced neural adaptations and compulsive drug use or even a correlation between drug-induced neural changes and an increase in preference for an addictive drug.

And this was in a recently published paper in a section headed “But Drugs Change the Brain”, in which he continued to debunk the “brain changes cause addiction” argument by saying:

There are no published studies that establish a causal link between drug-induced neural adaptations and compulsive drug use or even a correlation between drug-induced neural changes and an increase in preference for an addictive drug. For example, in a frequently referred to animal study, Robinson et al. (2001) found dendritic changes in the striatum and the prefrontal cortex of rats who had self-administered cocaine. They concluded that this was a “recipe for addiction.” However, they did not evaluate whether their findings with rodents applied to humans, nor did they even test if the dendritic modifications had anything to do with changes in preference for cocaine in their rats. In principle then it is possible that the drug-induced neural changes play little or no role in the persistence of drug use. This is a testable hypothesis.

First, most addicts quit. Thus, drug-induced neural plasticity does not prevent quitting. Second, in follow-up studies, which tested Robinson et al.’s claims, there were no increases in preference for cocaine. For instance in a preference test that provided both cocaine and saccharin, rats preferred saccharin (Lenoir et al., 2007) even after they had consumed about three to four times more cocaine than the rats in the Robinson et al study, and even though the cocaine had induced motoric changes which have been interpreted as signs of the neural underpinnings of addiction (e.g., Robinson and Berridge, 2003). Third [an analysis of epidemiological studies] shows that the likelihood of remission was constant over time since the onset of dependence. Although this is a surprising result, it is not without precedent. In a longitudinal study of heroin addicts, Vaillant (1973) reports that the likelihood of going off drugs neither increased nor decreased over time (1973), and in a study with rats, Serge Ahmed and his colleagues (Cantin et al., 2010) report that the probability of switching from cocaine to saccharin (which was about 0.85) was independent of past cocaine consumption. Since drugs change the brain, these results suggest that the changes do not prevent quitting, and the slope of [an analysis of epidemiological studies] implies that drug-induced neural changes do not even decrease the likelihood of quitting drugs once dependence is in place.

Read the full paper here – it’s an amazingly concise summary of the truths about addiction that contradict many of the accepted opinions pushed by the recovery culture – Heyman, G. M. (2013). Addiction and Choice: Theory and New Data. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 4. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00031

Why Does It Matter Whether or Not Addiction Is A Brain Disease?

When we accept the unproven view that addiction and alcoholism are brain diseases, then it will lead us down a long, painful, costly, and pointless road of cycling in and out of ineffective treatment programs and 12 step meetings. You will waste a lot of time without finding a permanent solution. When we examine the evidence, throw out the false disease concepts, and think rationally about the problem we can see that addiction is really just a matter of choice. Knowing this, we can bypass the rehabs, and find the true solution within ourselves. You can choose to end your addiction. You can choose to improv your life. You can choose to stop the endless cycle of “recovery” and start living. You don’t need to be a victim of the self-fulfilling prophecy that is the brain disease model of addiction. There are alternative views and methods of change which I hope you’ll take the time to learn about on The Clean Slate Addiction Site.

There are many different ways to argue against the brain disease model of addiction. I have only presented 3 basic arguments here. But beyond just addiction, many modern claims of “brain disease” are fatally flawed, in that they are founded on the logically impossible philosophical stance of psychological determinism. From this standpoint, any evidence of any brain activity is immediately interpreted as a “cause” of a particular mind state or behavior – with no regard for free will/the ability to choose one’s thoughts and thus behaviors. If you understand the impossibility of psychological determinism (or “epiphenomenalism”) then you’ll take all such claims with a grain of salt. For a detailed examination of this issue, see the following article: The Philosophical Problem with the Brain Disease Model of Addiction: Epiphenomenalism

How To End Addiction, Substance Dependence, Substance Abuse, Alcoholism, and General Drug and Alcohol Problems (updated 11/4/2015)

Due to the fact that most conventional rehab and addiction treatment programs follow the false belief that addiction is a disease, they are generally not effective at dealing with these problems – so I really can’t ethically recommend any “treatment” programs other than a run of the mill detoxification procedure if you feel you may be experiencing physical withdrawal symptoms – you can find that through your local hospital or emergency room; by asking your primary care doctor; or by calling 911 if you feel your life is in danger due to withdrawal (beware that withdrawal from alcohol and some prescription drugs such as the class known as benzodiazepines can lead to fatal seizures). But what comes after detoxification is simply personal choices, and treatment programs actually discourage productive personal choices by attempting to control people and feeding them nonsense such as the disease theory and idea of powerlessness.

If you want to end or alter your own substance use habits you need to make the choice to do so. Many readers will object to this answer as flippant, cruel, out of touch, et cetera. I realize this, but I chose to change, and in reality everyone who moves beyond problematic substance use chooses to change as well.

There is too much to unpack within what people believe is contained in the statement “choose to change.” I have tried to address some of that here in the past, but I realize this article is not the place to do that. This article’s scope needs to remain limited to the question of whether or not addiction is a disease.

My conclusion is that addiction is freely chosen behavior, and that the person who continues heavy substance use despite mounting costs still sees heavy substance use as their best viable option at the time they’re doing it – even though they recognize many costs and downsides. Choosing to change then, really means that they rethink whether heavy substance use is their best viable option. The only way I know to come to new conclusions is to re-examine the issues methodically, and this may often mean gathering new information and perspectives. Thus, the help that can be given to troubled heavy substance users is information. Helpers can provide accurate information that troubled people can use to change their perspective and come to believe they have better viable options than continued heavy problematic substance use.

I endeavor to give accurate information here that will help people to understand that change is possible, and that they are not doomed to a lifetime of addiction. Hopefully, this helps them on their way to believing in better viable options.

About this article:

I originally published this article on September 25, 2010. I have since added some significant supporting work I was able to find over the years, and those additions are noted. Some other minor edits from the original article are not noted.

Author

Hi, I’m, Steven Slate, the author of this post and of all content on this website. Yes, I was what you would call an “addict.” If you want to know more about me, go to the About page. If you want quotes from PhDs and such (as if I haven’t given enough here already) go to my Quotes From Experts About Addiction page. Please be civil in your comments, and many of your angry comments may already be answered on my FAQs page, so maybe check that out before you scream at me.

Literalism is the disease iself, not any endless ‘alcoholism’. When we learn to see ourselves as we really are, we see that the literalism that led to the drinking results in more of the same literalism. Two dimensional (literal) thinking does not address a world made of circles. Belief has never had anything to do with anything. Thinking is not seeing. The ‘choice’ refers to a choice to release the literalism, the thoughts, and learn to see. This has to do with epistemology. And it removes the sickness, because we see differently. The trance of literalism has been removed. Seeing is experiential. As long as one is committed to disease, they cannot take responsibility.

AA isn’t entirely unhelpful. It is founded on fundamentalism. Fundamentalism never heals a broken imagination. People in AA are ignorant of their own nature, stuck in belief. No one that identifies forever as sick or diseased is actually seeing themselves correctly.