A dramatic piece of addiction research used to prop up the brain disease model of addiction was blown to pieces this year: cue induced craving. You’ve probably seen this “science” portrayed on television over the years. Some very serious looking scientists in a quiet lab full of fancy equipment put a cocaine addict into a brain scanning device. They show him images related to cocaine use – pictures of people using, lines cut up on a mirror, and rolled up dollar bills and such (these are referred to as “cocaine cues”). Then they show us the brain scans, which show powerful spikes of activity at the moments when these cocaine cues are shown (this result is called “cocaine cue induced craving” as the brain activity is thought to represent the neurological activity behind craving). Sometimes, for good measure, they run the experiment with people who aren’t cocaine users, and the same neural responses aren’t found. This extreme brain activity in addicts, they say, is proof that addiction is a brain disease. It’s hard, indisputable scientific fact that addicts are “triggered” to use, and that the diseased brain takes over and “hijacks” the addict’s free will, forcing them to crave and eventually use drugs with no choice in the mater. Anyone who questions this is portrayed as the equivalent of a holocaust denier or flat-earther.

Here’s an example of some of that thinking shown in HBOs famous documentary on addiction, as espoused by Anna Rose Childress. It isn’t necessary to watch, just putting it here for sake of supporting what I’m saying. I’ve seen the same basic presentation many times elsewhere, but this was the only decent video clip of an example that I could readily find:

[Incidentally, there hasn’t seemed to be widespread use of Baclofen to treat addiction which was mentioned in that video as something that can supposedly suppress craving. It hasn’t become a “magic bullet for addiction.”]

After being shown these experiments for the past decade or two, we now get a new version of the experiment that blows the whole thing up. Previous studies compared bonafide “addicts” and non-users. But my favorite new experiment from 2017 looked for this same neural response in recreational cocaine users. They showed them cocaine cues, and put’em in a brain scanning machine just like Anna Rose Childress did in the video above. A press release on the study explains:

Researchers have known for many years that cocaine use triggers the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter involved in the brain’s reward system. In people with addictions, cues associated with drug use create the same effect. Visual cues— such as seeing someone using cocaine— are enough to trigger dopamine release and lead to craving.

Scientists have long believed that, as addiction progresses, cue-induced release of dopamine shifts to the dorsal striatum, a structure deep inside the brain extensively studied for its role in the way we respond to rewards.

“This area of the brain is thought to be particularly important for when people start to lose control of their reward-seeking behaviours,” Prof. Leyton says. “The dorsal part of the striatum is involved in habits— the difference, for example, between getting an ice cream because it will feel good versus being an automatic response that occurs even when it is not enjoyable or leads to consequences that you would rather avoid, such as weight gain or serious health hazards.” (McGill University, 2017)

The University announced the results of this study proudly:

Even among non-dependent cocaine users, cues associated with consumption of the drug lead to dopamine release in an area of the brain thought to promote compulsive use, according to researchers.

Analyzing the meaning of these results in Appendix B of The Freedom Model for Addictions, I wrote:

The traditional line of reasoning says that these neural responses are evidence of an abnormality in the brain which causes cocaine addicts to “lose control.” Now, here’s the rub— the researchers in this current experiment looked for the same brain response in recreational cocaine users, and they found it!

If both “compulsive users” (i.e., addicts) and “non-dependent cocaine users” (i.e., recreational users) have the same thing going on in their brains, then this can’t be evidence of a neural mechanism causing “compulsive use.” This brain activity isn’t a special feature of cocaine addiction; it’s a feature of liking cocaine, a fact which doesn’t do anything to establish or support the notion that cocaine use is ever involuntary. That is to say, it is evidence that people who like cocaine have these kind of neural responses to “cocaine cues,” and nothing more. You can have this response and be an “addict” or a recreational user.

What’s more, cocaine is the substance people quit most often without treatment; it is the shortest lived among all substance use habits and has the highest lifetime recovery rate (greater than 99%). Yet we’re routinely told that it has the power to create this special brain response that pulls people into a lifetime of addiction from which they can’t escape. Like so many of these claims about addiction, this claim is debunked, even before you get to analyzing the neuroscientific data, by simply looking at the real-world life results among “dependent” cocaine users. Nevertheless, that didn’t stop the university from concluding that the results found by its researchers should make us more afraid of cocaine than we were previously. They go on to say that:

The findings, published in Scientific Reports, suggest that people who consider themselves recreational users could be further along the road to addiction than they might have realized. (McGill University, 2017)

Or they just might like cocaine today, grow bored with it tomorrow, and eventually quit. The latter is extremely more probable since it is what more extreme users, the so-called “cocaine addicts” do in real life. Cocaine “addicts” (seen as people who are stuck with a lifelong obsession with cocaine, inability to quit, and a lack of control over the choice to use) don’t really exist in the way the recovery society has portrayed them. They quit, on average, quicker than any other “addicts”, they do so permanently, they do it most often without treatment, and they show the ability to choose cash rewards over cocaine in laboratory settings (Appendix A).

These results have gone unnoticed, I haven’t seen any other writers who are critical of the disease theory pick up on them yet. They’re very significant though. If even recreational users, who are considered to be “in control” of their cocaine use have these responses, then these responses are not the smoking gun in the case for the brain disease model of addiction that we’ve been told they are for nigh on 20 years now. They’re just a normal thing that happens when people like something. My favorite music genre is Drum & Bass. Throw me in a brain scanner and play some Drum & Bass, and you’ll probably see a neural response like that of a cocaine addict. It doesn’t mean that my practice of listening to this music is involuntary. It just means that I like it a lot.

“Like reading tea leaves”

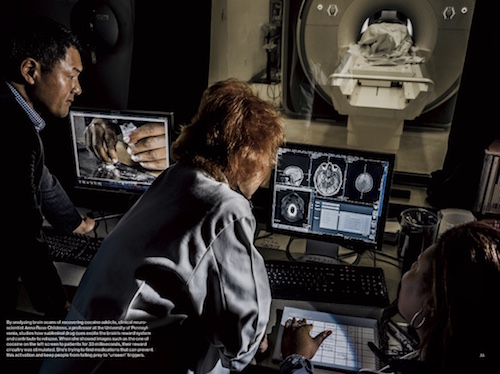

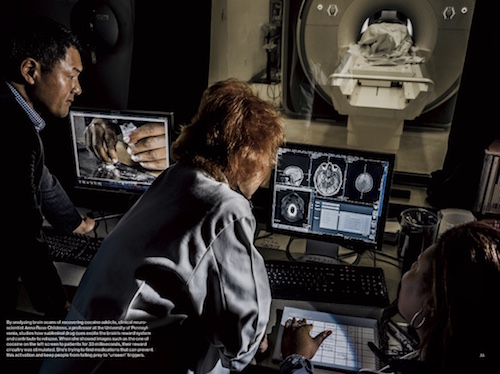

To put a hilarious button on the whole thing, just months after this study was released (april 2017) the September 2017 issue of National Geographic did a big issue on the promising new neuroscience of addiction. Anna Rose Childress was at it again:

Childress, who has flaming red hair and a big laugh, sits at her computer, scrolling through a picture gallery of brains–gray ovals with bursts of color as vivid as a Disney movie. “It sounds nerdy, but I could look at these images for hours, and I do,” she says. “They are little gifts. To think you can actually visualize a brain state that’s so powerful and at the same time so dangerous. It’s like reading tea leaves. All we see is spots that the computer turns into fuchsia and purple and green. But what are they trying to tell us?” [emphasis added]

Indeed. It is like reading tea leaves. All of this gazing at brain scans is being exposed as a useless superstitious exercise in proving something which has repeatedly fallen flat. People are able to stop using drugs when they want to. And when you talk to them about why they do it, they will give you reasons why they made the choice to quit. You’re not going to find peoples reasons in a brain scan, no matter how pretty it is, it’s just neural activity. It’s kind of looking at the gears of a car engine to discover why someone drove to visit their grandma. The superstition here is the idea that neurological data is more important than any other kind of data about why people behave the way they do. In the case of addiction, it’s really panning out to be the least important kind of data. It’s interesting, and I’m sure it must have some value, but our culture’s overwhelming focus on it is really doing troubled substance users a disservice. For example, watch the video above – where that poor man has been led to believe that his entire neighborhood will trigger him into involuntary cocaine use. That just isn’t helpful. In fact I think it must be very harmful. It creates a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Indeed. It is like reading tea leaves. All of this gazing at brain scans is being exposed as a useless superstitious exercise in proving something which has repeatedly fallen flat. People are able to stop using drugs when they want to. And when you talk to them about why they do it, they will give you reasons why they made the choice to quit. You’re not going to find peoples reasons in a brain scan, no matter how pretty it is, it’s just neural activity. It’s kind of looking at the gears of a car engine to discover why someone drove to visit their grandma. The superstition here is the idea that neurological data is more important than any other kind of data about why people behave the way they do. In the case of addiction, it’s really panning out to be the least important kind of data. It’s interesting, and I’m sure it must have some value, but our culture’s overwhelming focus on it is really doing troubled substance users a disservice. For example, watch the video above – where that poor man has been led to believe that his entire neighborhood will trigger him into involuntary cocaine use. That just isn’t helpful. In fact I think it must be very harmful. It creates a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Elsewhere in the National Geographic article, we get more evidence of the superstitious nature of conventional attempts at addiction science:

Wolfram Schultz, a University of Cambridge neuroscientist, calls the cells that make dopamine “the little devils in our brain,” so powerfully does the chemical drive desire.

Meanwhile, we get findings like oreos are more addictive than cocaine:

The “pleasure center” of the brain, the nucleus accumbens, apparently gets just as activated in response to Oreos as it does to cocaine and morphine, which could actually have some major public health implications. While the study was done in rats, the authors say it’s likely relevant to humans as well, and could explain why people have such a hard time resisting eating an entire sleeve of the cookies.

You may laugh, but that’s the point. The oreo findings (and others like it that have come out over the years as people try to prove everything addictive) give us perspective on the cocaine findings – they show that the cocaine findings are far less significant than we thought.

Addiction ain’t about the brain folks. It’s about people liking drugs and giving the drug experience a lot of meaning. When it ceases to have so much meaning for people, they move on. If you can help people to make discoveries and alter how much meaning and importance they imbue the drug with, then you can help them abandon reckless patterns of substance use. But telling them that they’re fragile and getting them focused on fearing and furiously trying to avoid an endless list of triggers isn’t going to help them. It’s going to distract them from real discoveries, and make them more fragile, as they continue running from the boogieman of addiction and giving the drug more significance in their life.