Addiction treatment workers complain about unethical behavior in the addiction treatment industry, in a recent New York Times article titled “How Staten Island’s Drug Problem Made It a Target for Poaching Patients.” Their target is rehab recruiters who offer backdoor referral payments for patients with private insurance. This is against the law in some states, but it gets done everywhere anyways. In fact, one of the complaints in the article is that agreements for referrals are worded in ways that circumvent existing regulations. Let’s look at some of the article’s deflective finger-wagging:

The outrage and supposed breach of ethics by rehabs

The director of a Staten Island treatment center says:

“They are opportunistic people or organizations who are preying on people of vulnerability at a time of high stress,” “It’s unethical. It’s borderline criminal.”

A representative of the state of New York addiction treatment regulatory office (OASAS) wonders:

“If you are referring a patient to somebody that is paying you, is it because they are paying you or because you believe the program is the best option for the patient?”

The article heavily features the director of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers (NAATP):

Particularly when profit is part of the equation, he said, pressure to fill beds could lead to unethical efforts to recruit patients. That possibility prompted the treatment providers association to create an ethics code two years ago.

Staten Island’s district attorney ignorantly jumps in on the demonizing and finger-pointing too:

Mr. McMahon said no one had brought the issue of payments for patient referrals to his attention. “Second only to the drug dealers who purvey this problem is someone who would try to take advantage of anyone who is ill,” he said.

A politician representing Staten Island ignorantly chimed in as well:

“The issue is disturbing,” said Mr. Donovan, who preceded Mr. McMahon as district attorney. “People may not be directed to the right resources for their ailments because someone is receiving compensation.”

The facts about addiction and treatment

Let’s get something straight: addiction treatment doesn’t work, it never has, and it never will. Data from Project MATCH, the US government’s biggest, most expensive study of addiction treatment tested three major treatment modalities (including Twelve Step Facilitation, which is used in nearly every addiction treatment program) and found that they had no clinically significant effect on people’s drinking. That is to say, the treatments don’t work. Comparing the treated participants to the untreated participants in the data, both groups fared almost equally well. See the full paper explaining that here, or my discussion of the relevant points here. A key finding was that the reduction in drinking occurs at week 0 of a 12 week course of treatment. That is, when people go through intake for a treatment program is when they actually cut down their drinking – note, week zero is BEFORE they’ve received any treatment whatsoever – which means you can’t even pretend to attribute the reduction in drinking to the treatment.

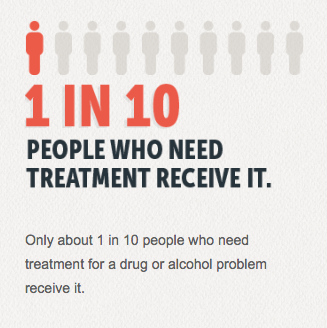

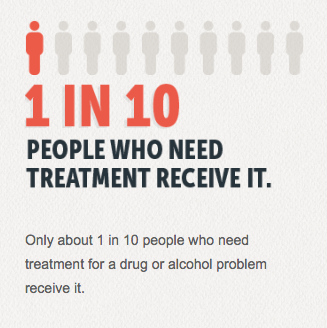

While the addiction treatment industrial complex laments the fact that “Only about 1 in 10 people who need treatment for a drug or alcohol problem receive it,” the fact is that 9 out of 10 alcoholics will get over their problem nonetheless. Epidemiological studies have routinely shown that untreated alcoholics have equal probability of “recovery” as treated alcoholics, and actually do better in some ways than those who “get the treatment they need” see one example of that data from the 2001-2002 NESARC survey. That study (together the 1992 NLAES) showed that at about any given time ~76% of people who’ve never been treated are over their alcohol dependence, while ~72% of those who’ve received treatment are over their alcohol dependence. This shows that treatment does NOTHING to improve rates of recovery. Consider it like a placebo study – if the same number of similar people get over a problem with a medication or a placebo, then you’d conclude that the medication is worthless and ineffective. Treatment is worthless and ineffective. What’s more, the untreated group appeared to recover quicker and for longer periods of time.

It really puts the claim that people “need treatment” into perspective, doesn’t it?

If you want to know some more precise numbers about the probability that someone will ever get over their substance use problem, a massive study carried out by the government found that:

Lifetime cumulative probability estimates of dependence remission were 83.7% for nicotine, 90.6% for alcohol, 97.2% for cannabis, and 99.2% for cocaine.

And as I wrote in 2013 when I covered the Suboxone craze, the numbers for opiates are similar:

More recent results from the NESARC data show that well over 90% of those categorized as heroin abusers or heroin dependent are currently “in remission.” LINK In these results, those who had ever been treated had slightly lower rates of remission. Although I can’t find the exact number in the study, one of the graphs appears to show that 100% of untreated heroin addicts (those classified as heroin dependent), are currently in remission!

The study also found that:

among individuals with PO [prescription opiate] abuse, those with a history of substance abuse treatment, on average, reported a lengthier abuse episode (41 months vs 23 months) and duration between first use and remission from the most recent episode (8.3 years vs 5.3 years) than the untreated; this difference was even more distinct among individuals with heroin abuse (treated, 83 months; untreated, 17 months) or dependence (treated, 69 months; untreated, 17 months).

So it appears that those who get treatment end up having addiction “episodes” that last longer than those who don’t receive treatment. This may be because treatment confounds the problem, and the powerlessness teachings deter attempts to change after “relapse.”

Where that data on opiate users differs from that data on users of other substances is that they seem to be far more likely to receive treatment nowadays. However, research on Vietnam Veterans who had been dependent on heroin showed that while upwards of 90% of them went untreated, upwards of 90% got over their addiction. For those who received treatment, the numbers were inverse. There’s nothing special about heroin use that demands treatment and treatment doesn’t work for heroin addiction any more than it does for any other substance (read – it doesn’t work at al). The only reason more heroin users end up in treatment is that heroin has a worse reputation than other drugs. It’s the big taboo.

One of the finger waggers mentioned in the NYT article worries that “People may not be directed to the right resources for their ailments because someone is receiving compensation.” What’s truly disturbing is that there are no “right resources for their ailments” because addiction is not a disease. Not being a literal disease, it literally cannot be treated.

As I argued in 2010, the brain disease model of addiction is nothing more than shoddy rhetoric dressed up with facts that sound “sciencey.” The con goes like this – do some brain scans and find differences between the brains of so-called addicts and non-addicts, discuss it in a bunch of technical neuroscience terms, then declare this proof that addicts can’t control themselves because of these differences, or as the brain disease proponents have said it often “drugs hijack the brain and rob the user of free will.” The problem with the brain disease model is that it never establishes causality between the neural adaptations and compulsive use or craving. And in fact, compulsive uncontrolled use has never been proven to exist itself (see Do addicts and alcoholics lose control?). As researcher Gene Heyman wrote: “There are no published studies that establish a causal link between drug-induced neural adaptations and compulsive drug use or even a correlation between drug-induced neural changes and an increase in preference for an addictive drug.”

When the brain disease propagandists show you the neural mechanisms that correlate with addiction or craving or whatever aspect of substance use, they’re not showing you causation. To wit, people quit using substances while their brains are changed in ways that we’re told compel them to crave and use substances. To be compelled is to be forced to do something, yet they stop. And they do it most often without medication. As neuroscience plows forward, we’re seeing that the formation of any skill or habit causes brain changes – yet we don’t consider most skills or habits to be addiction. The neural adaptations they show us to make the case that addiction is a brain disease are normal, everyday, routine neural adaptations that happen all the time. There is nothing “diseased” about such normal neural development. Disease is abnormality and dysfunction on a cellular level-which doesn’t exist in “addiction.”

The real ethical crime

In light of these facts, I’d have to say that “patient poaching” is the smallest ethical breach I could think of in the world of addiction treatment. Oh and by the way, what’s described in the article doesn’t even sound like what you’d think patient poaching would even mean. Here’s how “a volunteer at Carl’s House, a community center on Staten Island” described it:

“‘I know you guys need money,’” he said, recalling what a recruiter said in a recent call. “‘If you guys need funding, we can help you out. We can put you on a $5,000 donation a month, just call me whenever you get a private-insurance person.’”

Patient “poaching”?????? How can that be poaching? Poaching is stealing, it is theft. What you have here is an organization that probably serves mostly state-funded patients or charity cases, being offered a substantial kickback for sending the privately insured to private facilities, where, by the way, their private insurance will cover the costs. If I’m reading the situation correctly, the “poachers” should almost be commended. After all, if they’re opening space in the community center to serve disadvantaged people by getting the privileged out of there and into the centers the underprivileged can’t afford, aren’t they heros by these activists’ standards?

How is this a case of, as one treatment center director quoted in the article says “opportunistic people or organizations… preying on people of vulnerability at a time of high stress,” “It’s unethical. It’s borderline criminal.” How are they being preyed on? Because they might ultimately choose one ineffective treatment program over another ineffective treatment program?

Addiction is not a disease. Treatment doesn’t work. It can’t work, because you can’t medically treat a non-medical problem. Addiction is simply a strong preference for intoxication, which people learn to interpret as a compulsion (guess who they learn that from – treatment programs!). Again, 9 out of 10 people don’t get the treatment they supposedly “need” and yet about 9 out of 10 (or more) will get over their “addictions.” In response to the cries for people needing more treatment or the proper treatment, I call nonsense and ask “so what???” There is no proper treatment. Put them in any rehab using any treatment anywhere, and you’ll find little difference in outcomes, because treatment as a whole is no better than a placebo.

Addiction is not a disease. Treatment doesn’t work. It can’t work, because you can’t medically treat a non-medical problem. Addiction is simply a strong preference for intoxication, which people learn to interpret as a compulsion (guess who they learn that from – treatment programs!). Again, 9 out of 10 people don’t get the treatment they supposedly “need” and yet about 9 out of 10 (or more) will get over their “addictions.” In response to the cries for people needing more treatment or the proper treatment, I call nonsense and ask “so what???” There is no proper treatment. Put them in any rehab using any treatment anywhere, and you’ll find little difference in outcomes, because treatment as a whole is no better than a placebo.

The true breach of ethics is that anyone pretends to be able to medically treat addiction. Not only do they pretend to treat addiction, they spread the idea that nobody can quit an addiction without their help. This may be because of ignorance, but it is irresponsible to be so ignorant. The data on natural recovery has been available for long enough now that you really are practically a criminally negligent danger to society if you’re out there telling people they are unable to quit on their own. The entire treatment industry spreads this message constantly. Here’s an example of a doozy of a commercial I saw recently:

THIS is unethical. Studies have shown that belief in the disease of addiction is predictive of relapse. Studies have shown that those exposed to these messages by the recovery culture have higher binge rates after treatment. Seriously, can hysterical messages like the following be helpful?:

The idea she’s spreading is regular fare in treatment programs, and what’s worse, it’s demonstrably false according to research spanning several decades, going back to the 1960’s. THE 1960s. If you’re still spreading this crap, you are unethical. If you’re ignorant of the facts, then you shouldn’t be working to help people with substance use problems – staying at your job alone is a massive ethical breach because you don’t care to be informed about what you’re dealing with.

The treatment industry, its regulators (OASAS), and it’s trade guilds (NAATP) all know that addiction treatment doesn’t work. If they don’t know, then they should. But they know. It’s why they define success in terms of “retention rates” and “compliance” rather than in terms of reduction in substance use. They literally call treatments successful based on how many people keep attending their sessions – regardless of their substance use status. A near universal experience, going back decades now, is being a patient in a group counseling treatment session and having the counselor say “look to your left, and look to your right; only one of you will get sober,” indicating a 1/3 success rate. They know that what they’re doing doesn’t work, and yet they keep peddling it. This is the height of breaching your damn ethics. Yet what are they doing? Finger wagging at recruiters offering kickbacks for patients. This is deflection. They know they are all inherently unethical by virtue of the completely useless product they’re peddling. That, or they’re in denial of their addiction to carrying out a sick mass version of Munchausen by Proxy.

While more people are becoming aware that AA and 12 Step ideology doesn’t work, it unfortunately continues to appear, as this article points out, that the treatment industry, and medical profession as a whole, either refuses to admit that treatment doesn’t work or they know and they don’t care. Is it incompetence or cupidity? I would argue that it is a combination, but either way, for practical purposes, the issue is that the medical profession is offering treatment that is killing people and is very resistance to looking at this problem.

Thus, what has to happen is those that know how ineffective treatment is have to continue to scream as loud as we can (in figurative not literal terms) about this, and hope that sooner rather than later medical professions will start to care more about their patients than they do about their income.