Addiction treatment, and our entire approach to “addiction” doesn’t help, and it doesn’t “cure addicts”, it only creates more of the symptoms of “addiction” – hopelessness and a sense of powerlessness to change and make different choices. This what I chose to demonstrate when I got the chance to give a TED Talk on addiction. Here is the video of my TEDx Talk on addiction, and the text that follows is not a verbatim transcript, but rather my prepared remarks. You can also click this link to jump to supporting research at the bottom of the page. If you like the video, please share. I do this because I think this message helps people who struggle like I did in the recovery/rehab system:

PREPARED REMARKS:

I’m going to tell you something shocking today: addiction treatment doesn’t cure addicts – it creates addicts.

I study this, and I’ve lived it. I was a heroin user for 8 years; and ironically, the worst period in those years began immediately after I received treatment.

This defies expectations, because after all, treatment is supposed to help. To understand the principle behind why it doesn’t help, I’m gonna give you a quick example we can all relate to.

The Playground Effect, and how it works in addiction

You take your son to the playground. He’s running around with the other kids like an animal until he falls and bangs his knee. Usually, he’ll nurse the wound for a few seconds, then jump back up on the jungle gym – and maybe be a little more careful. There’s another way this can play out though. As you look on in horror, terrified that the child suffered a severe injury, he looks up, makes eye contact with you, and starts bawling.

The look on your face told him “this is a disaster.” He then experienced the minor injury as a disaster.

As we raise children, we falter sometimes, like on the playground, but mostly our goal is to find ways to make them believe in themselves. When they stumble and fall as they’re walking, we clap for the attempt. When they mispronounce words, we smile for the language they’re acquiring. We aim to empower them.

But with drugs, we teach them they have no power and that once they start, they’re forever enslaved. We tell them their desire to use drugs is tragic – and then they experience this desire as a tragedy.

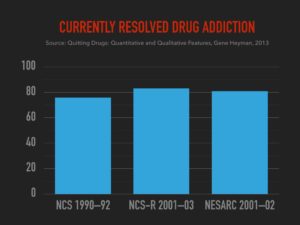

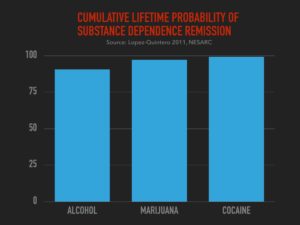

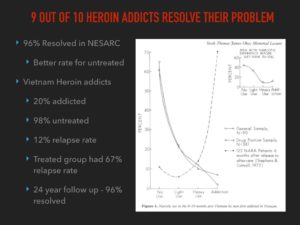

Most people’s drug use is not tragic though, and it doesn’t even fit the diagnosis for addiction. But the more surprising fact is that even the ones diagnosed with addiction usually don’t experience much tragedy. Only 1 in 10 addicts get treatment. Yet 9 out 10 of all addicts resolve their problems anyway. 90.6% resolve their alcohol problems; 97.2% resolve their marijuana problems; and 99.2% resolve their cocaine problems.

Moreover, Recent data showed 96% resolved their heroin problems. And of the Vietnam vets who were addicted to heroin in the war, 98% of them didn’t get treatment, yet only 12% relapsed. Recovery, without treatment, is the norm.

But when people receive treatment, things get worse. The Vietnam vets who received treatment had a 67% relapse rate. Following treatment, addicts typically struggle longer, relapse more often, binge more, and have increased overdose rates. The reason for this is that treatment programs are like that concerned parent on the playground. They send a clear message to the drug user that his problems are tragic and insurmountable.

How I became an “addict.”

When I went to rehab, they waged a relentless campaign to convince me that I was not choosing my own drug use. They told me I had to believe I had a disease that was forcing me to use drugs, and that if I ever used so much as a single hit or drink, I would continue using uncontrollably until I could get into treatment again. This is the norm in treatment, no matter how mild or severe your substance use.

In the off time when I wasn’t in a session, the counselors would send the experienced patients to convince me of my fate. I was 21 years old; these were heroin users in their 40s who’d been in and out of treatment programs their entire life. They’d tell me I have to admit that I’m powerless or I’d end up like them. That I’m in for a lifetime of craving. That I’ll only be able to deal with this by going to meetings and counseling for the rest of my life. They talked about how horrific withdrawal is, and how when you go through it, you’ll do anything to get more heroin. They made countless dire predictions about my fate – repeatedly saying things like “you’re not done yet,” and “you’ll be shooting up soon – they all do.”

Right after I left that rehab, I started using 4 times the amount of heroin I’d used prior to rehab. Before rehab I snorted heroin. Within a week of leaving rehab, I started shooting heroin.

Before rehab, I often ran out of money to support my habit, and went through withdrawal with much pain, but no compulsion to use. After rehab, withdrawal became completely intolerable. I reacted to it by doing anything I could to score more drugs. I started robbing my parents of everything they had, and running various scams such as shoplifting and passing bad checks. I had a short stint of homelessness, countless arrests, and even ended up in jail.

Before rehab, I was a very problematic heroin user, but I stopped and started at will several times over a 3 year period. I knew that I was in control of my actions, and that I was choosing my drug use. After rehab, I felt like I was hopelessly addicted, and that the rest of my life was going to be a struggle. There was a clear transformation that took place the moment I entered rehab: I learned to think of myself as addicted, and then that became my reality. It stayed my reality for the next 5 years while I went in and out of treatment.

Yes, addicts are in control. Even heroin addicts.

Now I realize I just dropped a bomb there. I said I was choosing my drug use; and this is heresy, especially with opiates, which we think of as the most addictive drugs. It is true that opiates can lead to physical dependence and withdrawal. But over thousands of years, countless millions of people have been dependent on them, and they detoxified without treatment. The physical symptoms of this withdrawal are identical to the flu. People come out of hospitals and go through morphine withdrawal every day, and yet they don’t feel compelled to seek out drugs. This is because they don’t think of themselves as addicted.

When Alfred Lindesmith carried out his famous study of opiate addicts in the 1940s, he found that the dividing line between those who become addicted, and those who do not, is a matter of belief and learning. He cited case after case where the turning point into addiction came when a well-meaning friend or doctor noticed that the opiate user was going through withdrawal, and said two magic words to him: you’re hooked.

This brings us back to the playground. Flu-like symptoms then become interpreted as an irresistible need for opiates. Essentially, a common cold is made into a fatal cancer – by the introduction of a fatalistic concept.

I’m not here to deny the danger of opiates; I’ve had several friends die of drug overdoses. But I blame these tragedies on addiction mythology. Lindesmith showed us 70 years ago, that ignorance to the concept of addiction, actually protects against addiction. But we didn’t listen. We’re constantly trying to convince people that they’ll get addicted. When we say “don’t let the doctor give you those pain pills, you’ll get addicted,” we’re probably causing more addiction.

The social and institutional processes by which we teach people to feel addicted.

We put substance users in a corner where they’re practically forced to start thinking of themselves as addicted. Through tough love and intervention, we threaten to withdraw love, support, visitation with family, and more – unless they identify as addicted, and go to treatment and support groups that foster this belief system.

I learned real fast in treatment, that I had better start talking the talk, or my family and the courts would not get a good report. My very freedom depended on acting like I was powerless. It didn’t take long for me to get lost in that role and genuinely feel powerless.

When we say substance use is a compulsion, we’re stigmatizing it, and the substance user. We’re denying his wants. In effect, we’re telling him “you’re not allowed to like that.” “Your preference is so wrong that it must be a disease.” We’re saying he’s a monster. Nobody wants to be a monster. So you become afraid to simply say you like it. Thinking of yourself as addicted becomes comforting and more attractive as a result.

So we’ve got a unique trap set up today. Everything we do and say to help people with substance use problems actually deepens their problems. It encourages them to feel as if they’re out of control, when in fact they aren’t. For those who are living under this terrifying illusion, there is a way out.

Unlearning addiction.

I told you that I transformed from feeling in control, to feeling out of control when I went to rehab and began to believe their message of helplessness. There was another turning point that was just as sharp – it came when I rejected that belief system.

My parents were begging me to get into another rehab, and I told them it was pointless unless they could find something truly different. They found The Saint Jude Retreat, whose website said in huge letters “Treatment Doesn’t Work!” They were billed as an educational program rather than a treatment program. I went.

When I arrived I was told that I didn’t have a disease, I wasn’t addicted, and that I could easily choose to change. This was what I had believed before treatment. They told me point blank that I was using drugs because I liked it, but that I might like life better without drugs if I gave that a real shot. They told me it didn’t have to be a lifelong struggle, but that it could be immediate. I know this sounds simplistic, and that many people think this is an offensive message. But to me, it was and still is a massive relief. They taught me to reject most of what I learned in treatment. The result was that I changed practically over night. I haven’t had heroin in over 14 years now. I haven’t struggled to resist cravings, and there is nothing that I do to battle addiction. I have felt fully free since I let go of the addicted mindset.

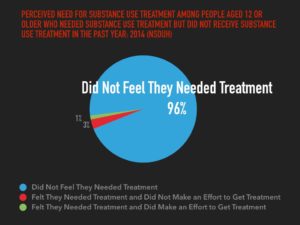

The popular approach to problematic substance use hasn’t worked, because it’s foundational premise is wrong. The very concept of addiction is that people’s substance use becomes involuntary, and they are unable to stop it on their own. 9 out of 10 people resolve their substance use problems, even though 9 out of 10 don’t get treatment – the majority are stopping on their own. When asked why they don’t get treatment, 96% of them say that they don’t think they need it. This is equivalent to saying they reject the entire notion of addiction. They think they can stop on their own, when they want, and indeed they do. Why aren’t we taking them at their word? When people end up in treatment saying “I can stop whenever I want,” why do we mock that? They can stop, but they prefer to keep using right now.

Heavy substance use is risky, costly, and sometimes ugly. Addiction is a concept we invented to explain away behavior and preferences that we’re simply uncomfortable with. Denial is the concept we invented to deny their preferences when they won’t play along.

Research has disproven addiction. When alcoholics have been given alcohol without their knowledge in the laboratory, they don’t proceed to drink uncontrollably. When methamphetamine users are given a hit of meth, then offered small amounts of money they can claim on a later date, they choose the money almost all of the time. You can’t pay an epileptic to not have a seizure, but you can pay a so-called powerless addict to not take drugs. This, and other research shows choice is fully in play. (see that data here, and a refutation of the brain disease model here)

The Freedom Model

For the past 5 years, I’ve worked in development for Saint Jude Retreats. The foundation of our approach explains heavy substance use better. We call it The Freedom Model, and the philosophy is that heavy substance users are freely choosing, and they prefer their substance use for simple reasons. They see benefits in it. That their preferences look costly or irrational to others is not a surprise. This is not unlike when people stay in bad relationships or dead end jobs. When they stay in such involvements, it’s because they think these are their best available options. The key to change then becomes re-evaluating, and seeing other options as more preferable. This fits all the research I’ve mentioned thus far. It’s the natural way people choose.

For the past 5 years, I’ve worked in development for Saint Jude Retreats. The foundation of our approach explains heavy substance use better. We call it The Freedom Model, and the philosophy is that heavy substance users are freely choosing, and they prefer their substance use for simple reasons. They see benefits in it. That their preferences look costly or irrational to others is not a surprise. This is not unlike when people stay in bad relationships or dead end jobs. When they stay in such involvements, it’s because they think these are their best available options. The key to change then becomes re-evaluating, and seeing other options as more preferable. This fits all the research I’ve mentioned thus far. It’s the natural way people choose.

So to help them, I don’t counsel or treat them – I present information, which first disproves the addiction mythology that has held them back, and then clues them into their power to choose. I also offer critical analysis of the perceived benefits of substances. When they see it as less attractive, using less is easy.

Where the addiction model is the concerned parent on the playground sending the child into panic and chaos, The Freedom Model is just straightforward, non-hysterical presentation of information that people can use to choose differently.

I’d rather people didn’t feel the need to come to me to begin with. Everyone is already capable of making these changes, and doesn’t need our program. It’s a matter of getting out of the addicted mindset, and all the information needed to do that is already out there, freely available to anyone. The more people see through the illusion of addiction, the less we’ll reinforce it. Then more people can join the successful majority who know they are capable of change.

We can help people with substance use problems, but it requires that we stop seeing them as addicts; and start seeing them as people with a strong preference for substance use that will most likely change.

Thank you

This was the prepared text for my talk at TEDx Tahoe City September 17th 2016. My writing process was hard, because I was trying to make a controversial case in 18 minutes. I went off script in the presentation, and may have suffered for it – I’m not sure yet. I will post the video as soon as it’s available. There were many points I would’ve loved to have given deeper explanation and supporting research for, but time surely wouldn’t allow. I also regret having to use the term “addict,” because I don’t think anyone is addicted (i.e. involuntarily using substances) and therefore no one is truly an addict. This is a learned social role only. Nevertheless, to communicate effectively and succinctly, I think I need to use the word at this point.

One of the organizers, Carolyn Hamilton, helped me immensely with my writing – showing me how to re-organize and sharpen it to pull the audience in. I think it worked! It was a great experience that I’m grateful for. I got plenty of eager compliments and questions after the talk. Response was fantastic.

Links to supporting research on my theme that addiction treatment creates addicts rather than curing addicts:

Vietnam heroin addicts results: Lee Robins 1993

“96% of those who don’t get treatment say they don’t think they need it” – National Survey on drug use and health

Review of epidemiological research on addiction, by Gene Heyman: Quitting Drugs: Quantitative and Qualitative Features

Why addiction isn’t a brain disease: Addiction Is Not a brain disease it is a choice by Steven Slate

Addiction isn’t a brain disease / no published papers establishing causation between neural adaptation and increased use / addiction isn’t chronic / >90% probability of recovery: Addiction and Choice – Theory and New Data by Gene Heyman

All substance use is voluntary: Do Addicts Lose Control? by Steven Slate

Withdrawal isn’t sufficient for addiction, and must involve belief in addiction: Addiction & Opiates by Alfred Lindesmith

Crack / meth users turn down another hit in favor of delayed cash: TED Talk by neuroscientist Carl Hart

Belief in disease model of addiction predicts relapse: What Predicts Relapse by William Miller

96% of heroin addicts currently in remission: NESARC Prescription Opioids and Heroin Results

The Making of Addicts

If I haven’t put enough of a point on the theory I’m presenting here, it is this:

Many people have a strong preference for substance use. They don’t feel powerless or addicted until they learn to interpret their preference as an addiction. They learn this interpretation both inside and outside of treatment programs – by both social and institutional processes.

The work that opened my eyes to this particular explanation was The Making of Blind Men by Robert A Scott. He’s a sociologist who studied the plight of the blind under the care of blindness organizations. The parallels between what he saw in that world, and what I see in the addiction recovery world are uncanny. He presents blindness (as a state of helplessness and dependence) as a learned social role – as a way that people learn to interpret and experience their sight loss. I highly recommend this book. For one example of the parallels, note that many blindness organizations believe the blind must first “accept” that they can never live any semblance of a normal life and never function independently, before they can be helped at all. This set off alarms for me, echoing the message that addicts must accept that they have a disease and are powerless, before they too can be helped in any way. Seeing these principles in action outside the recovery world makes everything crystal clear.

Great job, thank you for giving this talk.

I don’t understand why, but the comment box for this site is only letting me type in all caps. I’m hoping this doesn’t come out as if I’m screaming, but I sort of expect it will.

This is a great topic; thank for you giving this talk and illuminating a grossly misunderstood effect of “the treatment industry.” I recently got out of a traditional Intensive Outpatient Rehab program. Here’s a quote, word for word, in our handbook: “Addiction is a chemical/biological disease that is primary, progressive, chronic, and fatal.” In one group we read this hilarious, page-long poem called “I’m Your Disease.” Here’s a bit:

“More than you hate me; I hate all of you who have a 12 step program. Your program, your meeting, your higher power all weakens me, and I can’t function in the manner I am accustomed to. Now I must lie here quietly. You don’t see me, but I am growing bigger than ever.”

Near the end, the counselors were teaching about relapse. In rehab, patients are taught that relapse begins weeks and even months before that first drink. Is it any wonder that people relapse when they’re taught that they can never feel safe, that they’re always under the thumb of their diseased thinking, which continues to get worse even as they progress into a sober life? Is instilling this sort of fear really, this lack of trust in self, the best we can do to help people achieve their goal of sobriety? I think not.

Thanks to your blog and some personal insight of my own, I’m working on de-programming myself on a whole new level (I have already thoroughly de-programmed myself with regard to AA, the disease model, etc). Whenever I have what I would typically consider “a crave,” I take a step back, and dissociate the feeling from the idea of “an alcohol craving.” I identify the underlying mood/feeling/circumstance (for example, I’m feeling uneasy because I’m putting off something important) and treat it just like it’s a normal thought that any person would have. From there I can figure out a rational approach that is sure to make me feel better; I no longer believe that alcohol has that power, even in the short term. I think it’s easy to get into the habit of condemning feelings as cravings, while often they’re perfectly healthy, even for somebody who hasn’t had issues with addiction.

Anyway, that’s what is on my mind tonight. Thanks again, Steven.

Thanks for telling your experience in treatment. The general public just doesn’t know the awful things that are taught there. I’ve seen that entire poem too, and it’s a doozy. A popular recovery saying sums it up “while you’re in here (a support meeting), your disease is doing pushups in the parking lot.” This is utter nonsense, and contradicts the epidemiological data which conclusively shows that people do get over these problems permanently for the most part. Addiction rapidly declines with age, which shows that it is not chronic – it’s a phase.

I was confused by the comment entry boxes showing all caps too – I just finally figured out how to fix them, which was a personal feat because I know nothing about web design!

Thanks Steven for spreading the word about addiction stereotypes. I am living proof of the damage an addiction label can cause. I was sober for 6 years and was unhappy for most of it. After ending my sobriety a year ago my life changed dramatically. Right now I am the happiest/strongest I have ever been, but not because I am drinking. I am strong because of the way I feel about myself after conquering “addiction”. There is no way I could of felt this way if I was wrapped up in negative AA messages and inaccurate AA information. Feeling like I was an “addict” made me feel weak and withdrawn from the world. I truly feel if someone is abusing substances they can recover if they make serious life style changes. You have to understand why you abuse substances in order to make positive changes. I made positive lifestyle changes and now that the recovery process is over I can go back to living a normal life WITH drinking. I took my power back when I “relapsed”. I want to clarify one thing before I end my comment. I do not condone getting hammered just because your not an addict anymore and everyone’s recovery is different. My message is to the people who were serious about their recovery and are stuck in “recovery culture”. The best decision I ever made was to rebel against the entire AA culture and break free of “addiction”.

Sincerely, Jonathan Cameron