I had the opportunity to see a screening of The Business of Recovery in NYC last month. Here is my extremely brief review and recommendation, followed by a lengthier criticism.

The Business Of Recovery was a high quality production. It covered several topics in ways that we don’t normally see in most mainstream reports about the treatment world. It was critical of the disease model and the dominance of the 12-Steps in addiction. It got some great soundbites out of recognized experts, most notably, William Miller citing his own 1996 study that demonstrated the most potent predictor of relapse is belief in the disease model of addiction. Miller also featured heavily in a segment debunking the buzzword “Evidence Based Treatment” and that was refreshing to hear. I’ve been bothered by that term for years (see my 2012 article Is Twelve Step Facilitation Really An Evidence Based Treatment). I was also delighted to see a takedown of the certification associations who put their stamps of approval on various rehabs, another issue I haven’t really seen anyone else take on. Bravo.

Those, and more, are all great points which the public would do well to learn, and this film communicates them well. Business should therefore be watched by whomever has the slightest interest in the topics of addiction and recovery, and then you should recommend the film to others. It is well done and could definitely open many eyes.

If you want to see this great documentary, visit their website TheBusinessOfRecovery.com and their Facebook page for more info.

If you want to see this great documentary, visit their website TheBusinessOfRecovery.com and their Facebook page for more info.

There are some issues with the film though. Now onto those issues.

You can medically treat diseases. You can’t medically treat non-diseases.

One of my hopes for a film like this is that it would give people pause about proceeding with “treatment” for addiction. After all, the film criticized the disease model of addiction – and if addiction isn’t a disease, then what are you treating? Right? Am I crazy for following this train of logic? I don’t think that I am. I work in an educational program that offers people information about motivation, choice, substance use, models of addiction, et cetera. Our institution (Baldwin Research Institute) has come down firmly against the disease model of addiction. Therefore, the help we offer is not treatment. It can’t be. [our help is education]

Yet I see people miss this point completely all the time. I see commercials for Passages Malibu, a treatment center who claims rightly that addiction is not a disease, and then moments later brags that they offer the most advanced treatment for addiction. Which way is it? You can’t have your disease and eat it too.

There are others besides Passages. The non-12-step world is full of people who seemingly fight the disease model, and then cry for more treatment. At this screening, the filmmaker gave a talkback, and demonstrated that he too was in this camp. He shat upon conventional treatment, and when pressed for what he thought were the advanced scientific evidence based treatments, he indicated that he favored pharmaceutical options such as methadone. So it’s not a disease, but let’s treat it with medicine!

The audience seemed to be in agreement that the privileged people in the film shelling out dollar amounts ranging from the tens of thousands to the millions of dollars were clearly getting nothing for their money. A woman from the audience who agreed the treatment wasn’t working then subsequently asked the filmmaker why he didn’t address the fact that there are so many poor people who can’t get this same treatment! She was outraged that poor people weren’t also getting this same, ineffective, waste of everyone’s time, ripoff of a treatment.

Such is the nature of any public discussions of addiction – people rhetorically running around like chickens with their heads cut off. “The treatment doesn’t work! Addiction isn’t a disease! But… we need more money to get people all of this great treatment. They NEED it!”

Unfortunately, this contradiction floats unnoticed in every gathering of addiction activists believing themselves to be oh so very progressive. This film is no exception.

What Vivitrol???

The filmmaker indicated his support of pharmaceutical treatments at the Q&A, and yet they weren’t mentioned in the film. Like, they weren’t mentioned at all. Usually, the people clamoring for these supposedly great advanced treatments are talking about pharmaceuticals, so it was odd they weren’t mentioned in the film. But even more odd than that was that they sat right there on screen in the film – seen by everyone, but mentioned by no one. Sorta like a cold sore. I knew something was amiss before he even got to mention his belief in these treatments.

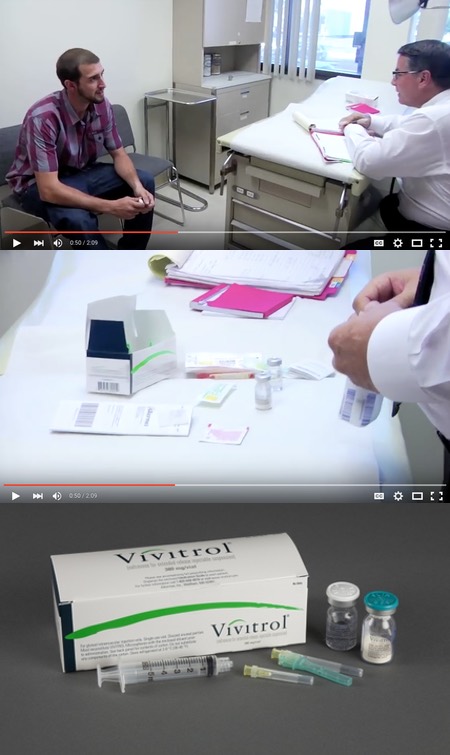

The film featured an ongoing storyline about a boy in his early twenties, Michael. He’s the first person shown in the trailer below, have a look:

The film goes into depth about how many rehabs Michael attended, and how much money his family has spent on these treatments. It is obviously a tragic waste and shame, and his story unfortunately isn’t unheard of among affluent young people in the treatment system. Most of his interviews take place while he’s in the office of Stuart Finkelstein M.D., an addictionologist, who is treating Michael with Vivitrol (an injectable version of Naltrexone that lasts for one month and blocks the effects of opiates).

Again, the film is an indictment of the treatment system being unscientific, and centered upon the 12 steps. It also takes on the disease model of addiction. Toward the end of the film it seems to endorse SMART Recovery and the treatment offerings/recommendations of Lance Dodes and Tom Horvath – both of which are decidedly not 12-step oriented – as the more scientific treatments available. Then in the Q&A, the filmmaker demonstrates his fondness for pharmaceutical treatments. But never mentions them in the film.

What about that Vivitrol though? Despite showing more than one person in Dr Finkelstein’s office with a box of Vivitrol sitting next to them, this drug is never spoken of in the film. I happened to recognize it sitting there in the shots of the doctor’s office, and then I asked the filmmaker one question after the film was over: “Was Michael being treated with Vivitrol in those doctor’s office scenes?” To which he answered “Yes.” and moved on to the next question.

I can’t say for sure what the filmmaker was planning for his film, but as a viewer and person who is knowledgeable about addiction treatment, I saw that Vivitrol sitting there; I saw criticisms of backwards non-scientific treatment approaches; and I saw a sad case getting what looked like it would be a successful treatment from an expert who was given tons of screen time in the film and treated with respect by the filmmaker; and I subsequently expected a happy ending with Vivitrol.

I got the opposite. By the end of the film Vivitrol hadn’t been mentioned, and it was reported that Michael tragically died just months after his interviews shot in Dr Finkelstein’s office next to that box of Vivitrol.

To me, it seems that they had a medication storyline planned for the film, and when it didn’t turn out how they expected it to, they just scrapped it and never mentioned it. Why wouldn’t they mention it? They were indicting treatment, and here was yet another treatment that had no effect. And Vivitrol ain’t cheap. It reportedly costs over $1000 a month, making it fit even better into the overall theme of their film. I can only assume they still have faith in this treatment and that’s why they didn’t mention it. I could be wrong, but I saw something similar in The Clinic and Elsewhere, which was an ethnography which followed 12 buprenorhine patients for 3 years, only to find no success, but to bury this result under a bunch of intellectualizing and philosophizing (I reviewed that book at Amazon, and discussed it more in an article on Bupe and other maintenance drugs for this site).

There’s plenty of story to be had with Vivitrol. It is a long lasting injectable form of Naltrexone. It’s a blocker, which means that it blocks the brain’s opiate receptors so that opiates can’t get in there to make you feel their effects. That is, it makes it so you can’t get high. Some people thinks this means it will also stop “cravings.” The message boards where users advise each other on these drugs tell a different story. Look at a few posts from one such board:

i took the vivitrol shot almost 30 days ago. and i have been trying to get high for the past week, and still cannot feel a thing. im not ready to quit and im obsessing over the idea of using. i am a heroin addict and i want to feel the rush! how long do i have to wait for the vivitrol to wear off??

thanks.

and…

Come on, can someone please respond to this, i have been on the vivitrol shot for a long time and i just am not cut out for this shit. i was ment to die alone thinking about the next come-up , i cant take it anymore. I feel like im developing a psychotic disorder, Btw im 2-weeks into my 3rd shot and anyone whos reading this and all those liers out there that keep telling you not to relaspe because you will, “feel better in time” thats bull f***in-shit

And there are plenty of more people out there online complaining of the mental torture of wanting to get high but being unable to. Some take dangerously large amounts of drug to try to do so. This is no panacea, nor are the many other pharmaceutical treatments for addiction that we’ve seen through the ages. This includes heroin, which was at first considered a treatment for morphine addiction, and touted as such by the intellectuals of its time:

In 1898 the German Bayer Laboratory, a major pharmaceutical company, introduced a new morphine derivative that had been discovered two decades earlier. This new drug was three times as potent as morphine and was marketed as a nonaddicting substitute for morphine or codeine. It was named heroin for these “heroic” properties. Physicians writing in medical journals described it as a nonaddicting drug. A paper in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal asserted that “there was no danger of acquiring a habit” (cited in Szasz, 1974, p. 179). The New York Medical Journal (Manges, 1900) dismissed missed its addiction problems as minimal:

Habituation has been noted in a small percentage … of the cases. . . . All observers agreed, however, that none of the patients suffer in any way from this habituation, and that none of the symptoms which are so characteristic of chronic morphinism have ever been observed. On the other hand, a large number ber of the reports refer to the fact that the same dose may be used for a long time without any habituation. (Quoted in Ray, 1978, p. 308)

-Peter Conrad. Deviance and Medicalization: From Badness to Sickness

Now, I’m not saying the filmmakers had to go so in depth as all this on the pharmaceutical treatments for addiction. That topic could easily make it’s own full movie, or even a mini docu-series. But I am saying it is a major problem of this film that they didn’t so much as utter the word Vivitrol or Naltrexone after showing this boy in that doctor’s office being treated with it, and then having him turn up dead by the end of the film. This topic is conspicuous in it’s absence, and mars an otherwise good exposé of the treatment industry.

(Note: after publishing this article, someone involved in the film confirmed that indeed they were doing a storyline on Vivitrol, and it was abandoned)

WIth the lack of mention of such medications, I presume the film skipped over mentioning yet another common and dangerous practice in 12-step groups, of telling members and newcomers that they are “not sober” (the ultimate sin in 12-step culture) if they are taking medicine prescribed to help them stop drinking/drugging, or prescribed for any psychiatric purpose, and actively encourages them to STOP taking such prescribed medications. As many have been told, “AA is all you need,” and “doctors and shrinks don’t know about the disease of alcoholism, we do.” AA World Services actually admits that this happens, in the pamphlet described here:

http://nadaytona.org/alcoholics-anonymous-admits-aa-members-role-in-suicides/

The irony of the alternative, uh, “treatments” saying addiction is “not a disease” yet they offer treatment reminds me of what I’ve read many AA members say in comment sections on addiction related articles, that AA is “not treatment,” but they constantly talk about “this disease of alcoholism” and “this disease of addiction.” They may not tell newcomers in meetings that AA “is” treatment, but they DO say alcoholism IS a disease, and that “AA is all you need” to recover and put the disease into remission.

I have an Atlanta metro area meeting list circa 1990 that has several paragraphs telling all the things AA does NOT do, such as not offering medical, psychological or psychiatric services/treatment, not offering religious services, etc. Yet it’s quite arguable that AA meetings and AA sponsors indeed do many of these things.

Yes, it’s quite ironic isn’t it! Everyone is trying to have it both ways.

One can certainly have a medical condition that is not a disease and therefore receive medical treatment. A broken leg isn’t a disease yet requires treatment of some kind in order to properly heal. Sorry this is a specious argument to me though I appreciate the idea. (Full disclosure: I’m also in the film). Dee-Dee Stout, consulting health counselor/professor/author, “Coming to Harm Reduction Kicking and Screaming.”

Hi Dee Dee,

First, I sincerely thought you were great in the film.

Second, I meant “medical condition” when I said disease.

I’m not a great writer. I take too many detours and tangents, and worst of all I often try to write things that are impenetrable, with every asterisk denoting every nuance and exception so that I don’t have to fend off those attacks later. The result when I do that though, is unreadable. So over the past few years, I’ve tried to get away from that. I had the thought “maybe I should explain what I mean by disease or just use the term medical condition” before publishing this article. But then I remembered that I’m trying to get away from that kind of defensive writing.

So yes, disease isn’t the only category of medical problem – we agree. However, I think that when we’re debating the issue of whether or not addiction is a disease, we’re debating whether it’s a problem of physiology – cells, neurons, neurotransmitters, etc; or whether it’s a problem of choice – ideas, awareness of options, values, evaluation of costs and benefits, self-esteem and self-efficacy.

I don’t think it’s a disease, and I don’t think it’s akin to an injury like a broken leg, or some other physiological issue like a callous or wart or something. I don’t think it relates to physiological conditions (although, and here I go with my defensive writing – withdrawal syndrome is a physiological problem/medical condition – withdrawal syndrome, however, is not addiction – it is withdrawal syndrome). I don’t think it’s physical, so I don’t think it’s medical, and so I don’t think it can be medically “treated.”

That isn’t to say that I don’t think therapists and counselors have any good insight, information, or frameworks to offer. I think they can. But I think those things need to stop being attached to the idea of medicine – i.e. they need to stop being called treatment. Treatment implies that some process outside of yourself is fixing you. But in fact, there is an internal decision making process by which everyone, and I mean everyone, who moves beyond “addiction” does so – whether they happen to take a medication, see a therapist, go to a rehab, or talk to me while they also independently make their decision to change.

-Steven

Do you think PTSD is a medical condition? I think our understanding of how the brain works is lacking. Therefore, claiming addiction is absolutely not a medical condition is an opinion reached without all the facts.

Benjamin Rush, a very prominent Founding Father physician, was one of the first in the West to label excessive alcohol use and chronic intoxication a disease. Of course, he also called black skin and homosexuality diseases and managed to cure people with toxic purged, bloodletting and mercury.

‘To be a disease, or not be a disease’… matters today because there is money in it for too many people. Until reproducible empirical scientific evidence is demonstrated, we should all agree to refer to it as an unproven theory and save a lot of money.