The number of Americans who fit the diagnosis for a heroin/opioid addiction (Opioid Use Disorder or OUD) is currently 2 million (most recent data available is from 2018). It has hovered around this number for a long time, with a low of 1.7 million in 2002, and a high of almost 2.4 million in 2015. According to data from an FDA drug review and other sources, a million or more patients a year have been taking buprenorphine acquired through pharmacies rather than traditional addiction treatment services since 2012. Since 2006, more than half of patients diagnosed with OUD by office-based doctors (not in addiction treatment clinics) have received buprenorphine, and by 2015, almost three quarters were receiving it. Half or more of annual buprenorphine patients are starting a new episode of treatment, meaning they would most likely be counted as people currently diagnosed with OUD.

Regardless of these facts, media representations often give the impression that buprenorphine is underutilized or even especially inaccessible as a treatment for OUD. They suggest that most people with OUD cannot or are not getting this medication. For example, here is a New York Times Op-Ed that gives this impression, and a Pew blog that does the same. They claim that only 20 to 25 per cent of people with OUD receive any treatment, while far fewer receive buprenorphine, for example, as Dr Sarah Wakeman wrote in 2019:

Despite their effectiveness, a new report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine found that only 5% of people with opioid addiction received medication treatment in 2017.

Medication can treat opioid addiction, but this is why most people don’t get it; The Tennessean , May 2019, Sarah Wakeman and Ryan Hampton

This messaging is ubiquitous amongst buprenorphine-centered addiction activists on social and traditional media. In addition, they focus on the fact that doctors must receive a special waiver (the x-waiver) to prescribe buprenorphine for addiction. They often cite statistics showing that only a small percentage of doctors have the x-waivers, and further, that a large percentage of rural counties have no such waivered doctors. This is followed by calls for deregulation of buprenorphine prescribing (the motto is “x the x-waiver, see the hashtag on twitter) to increase access. The implication is that if only more people could get buprenorphine, overdose deaths would drop dramatically. For example:

Would deregulation work? After France instituted this approach in 1995, deaths from opioid overdoses dropped nearly 80 percent. A similar drop in the U.S. would mean 37,000 fewer deaths from opioid overdoses in 2017. It’s true that the U.S. is not France. All French citizens have health insurance and Americans with insurance pay much more out of pocket. But even if deregulation of buprenorphine prescribing led to “just” a 50 percent decrease, that would mean 20,000 fewer deaths.

Deregulating buprenorphine prescribing for opioid use disorder will save lives, By Kevin Fiscella and Sarah E. Wakeman March 12, 2019

The suggestion that we follow France is often accompanied by the claim that a tenfold increase in buprenorphine patients would solve the overdose crisis:

France, facing increasing heroin use in the 1990s, deregulated buprenorphine, permitting doctors to prescribe it without extra training or licensing. The policy change reaped immediate benefits. Ten times more patients received addiction treatment, and within four years, opioid overdose deaths decreased by nearly 80%. Even if the U.S. could only partially replicate this success, we could save thousands of lives.

Congress should back buprenorphine bill to stem opioid crisis | Opinion; Robert Bonacci, for the Philadelphia Inquirer May 16, 2019

There can be no doubt that deregulation would make buprenorphine easier to access, and in my opinion, this would be of great help to opioid users at moments of crisis. However, the premise that barely anyone can access it is wrong in the first place. Plenty are accessing it under the current restrictions. As you will see, we have had something near a tenfold increase in prescribing, similar to France, even without deregulation.

At this point, the percentages of people with OUD who receive buprenorphine treatment annually dwarfs the percentage of patients with other SUDs (Substance Use Disorders) who receive “specialty treatment” (treatment delivered by addiction treatment programs licensed and overseen by government). Overall, amongst all people with SUDs, only 11% receive specialty treatment annually. Amongst only people with OUD, as the Pew blog linked above mentioned, 26% receive treatment (approximately a half million people) from specialty treatment services annually. This includes those who attend classic inpatient rehabs, outpatient counseling clinics, methadone clinics, and those who receive buprenorphine from those and other similar services whose primary activity is addiction treatment and are overseen as addiction treatment services by government agencies. In 2017, these “specialty treatment” providers were treating 112,223 people with buprenorphine on the date data is collected annually. Given there were somewhere around 2 million people with OUD, looking at this figure only would make it appear that 5% are being treated with buprenorphine.

Importantly though: this doesn’t count those with OUD who receive buprenorphine through traditional doctor’s visits and trips to the pharmacy. While not unregulated, doctors who prescribe buprenorphine outside of addiction clinics are not considered “specialty treatment” and thus their patients are not counted by the sources commonly cited by Wakeman and others. Patients receiving buprenorphine from doctors outside of specialty treatment represent at minimum another half a million people (as you will see in data cited below), bringing the percentage of people with OUD receiving addiction treatment of any kind annually to at least 50%. The overall percentage of all OUD patients receiving any kind of specialty treatment, as well as the subgroup being treated with buprenorphine by office-based physicians is far greater than the overall rate of annual treatment utilization for people with any other SUD.

By omitting, overlooking, or simply forgetting the patients treated with buprenorphine outside of specialty treatment, many activists are giving us an extremely incomplete picture of opioid addiction treatment. The case that buprenorphine is underutilized or inaccessible to most is thus extremely flawed. This post was written to help give a more accurate picture of the utilization of buprenorphine in the United States. To understand how many people are actually being treated with it, we need to know how many are getting it through the standard doctor/pharmacy route.

I’ve compiled some data from various sources over the years to fill in this gap of knowledge, and have recently found some new estimates. Here it is.

Number of patients receiving buprenorphine from office-based physicians and pharmacies:

Several sources have given numbers of how many people get buprenorphine prescriptions in pharmacies, for various years. Here are the numbers (sources at bottom of section):

- 2003 – 20,000

- 2006 – 150,000

- 2009 – 600,000

- 2010 – 800,000

- 2012 – 1,000,000

- 2014 – 1,300,000

Buprenorphine can also be used for pain relief, but this is said to be a rare practice. So those figures may include some patients who aren’t using it as an addiction treatment. The sources for the 2003, 2009, 2012, and 2014 figures do not denote whether or not they include patients taking buprenorphine for pain. [UPDATE: recently released figures show that 4.7% of buprenorphine is prescribed for pain (Currie 2021).] However, the 2006 and 2010 figures are specifically about prescriptions for addiction treatment, according to DHHS:

According to the DEA Automated Reports Consolidated Orders System (ARCOS), over 190 million dosage units were distributed to pharmacies in 2010, a more than fourfold increase from the almost 40 million dosage units distributed in 2006. It should be noted that only 1.1 million dosage units were distributed to OTPs during 2010. In addition, almost 800,000 individuals received buprenorphine addiction treatment prescriptions from office-based physicians in 2010, increasing almost fivefold from the 150,000 estimated in 2006.

DHHS in Federal Register, Volume 77 Issue 235 (Thursday, December 6, 2012)

You might be shocked at those numbers if you’ve heard that buprenorphine is drastically underutilized or unavailable as a treatment for addiction. The reason for this is that most who say it is underutilized base their claims on its use in Opioid Treatment Programs (OTPs), without considering how much is being prescribed by doctors not affiliated with OTPs and other specialty addiction treatment programs. As you can see in the quote above, the 190 million doses of buprenorphine prescribed by office-based physicians in 2010 was far greater than the 1.1 million doses dispensed by OTPs.

An important note: A recent letter to JAMA (Olfson 2020) gives some figures for office-based patients that differ significantly with these. This is covered later in the post.

Sources:

2003 and 2009 – CESAR FAX (Vol 20, Issue 22). (2011). University of Maryland Center for Substance Abuse Research.

http://db.cesar.umd.edu/cesar/cesarfax/vol20/20-22.pdf

2006 and 2010 – Federal Register (Volume 77 Issue 235). (2012). Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2012-12-06/html/2012-29417.htm

2012 – Skeete, R. (2015). Probuphine New Drug Application 204442 (Clinical Review No. 3295163). Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2016/204442Orig1s000MedR.pdf

2014 – Skeete, R., & Travis, J. (2016, January 12). Efficacy and Safety of Probuphine for the Maintenance Treatment of Opioid Dependence in Clinically Stable Patients. Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC) Meeting, US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/media/95578/download

Currie, J. M., Schnell, M. K., Schwandt, H., & Zhang, J. (2021). Prescribing of Opioid Analgesics and Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorder During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 4(4), e216147. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.6147

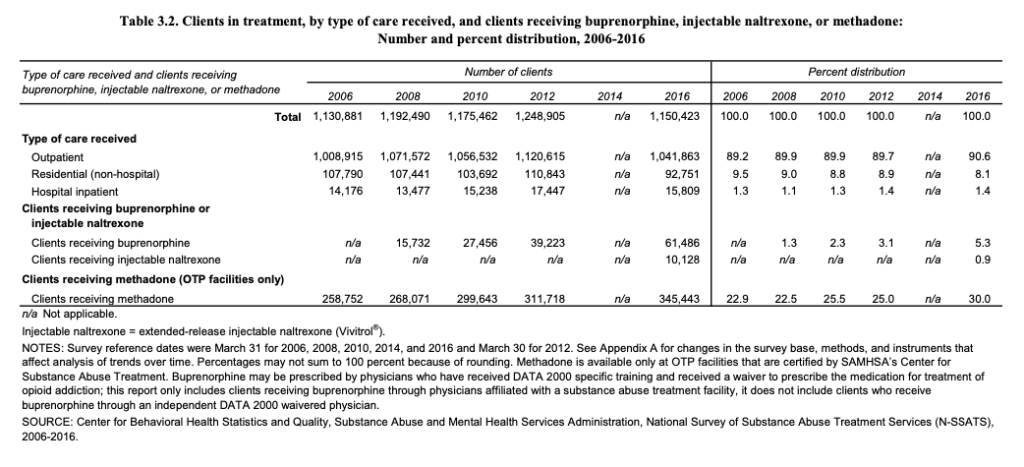

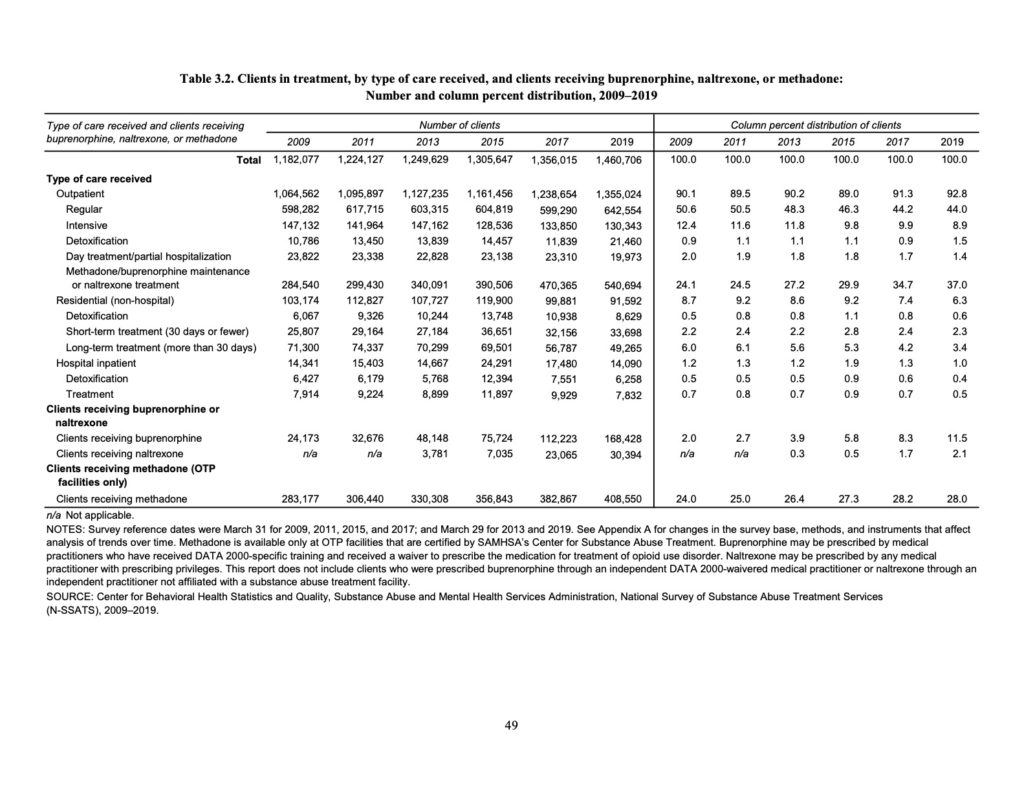

Number of patients receiving buprenorphine from OTPs and other specialty addiction treatment sources:

The 2016 AND 2019 National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS) gives numbers of patients receiving buprenorphine in specialty treatment programs such as OTPs for most years in the time range mentioned above. I’ve put the available specialty treatment figures alongside the known office-based patient numbers below:

| YEAR | SPECIALTY TREATMENT BUPRENORPHINE PATIENTS | OFFICE BASED BUPRENORPHINE PATIENTS |

| 2003 | NA | 20,000 |

| 2006 | NA | 150,000 |

| 2008 | 15,732 | NA |

| 2009 | 24,173 | 600,000 |

| 2010 | 27,456 | 800,000 |

| 2011 | 32,676 | NA |

| 2012 | 39,223 | 1,000,000 |

| 2013 | 48,148 | NA |

| 2014 | NA | 1,300,000 |

| 2015 | 75,724 | NA |

| 2016 | 61,486 | NA |

| 2017 | 112,223 | NA |

| 2019 | 168,428 | NA |

As you can see these numbers are much smaller compared to the office-based physician patient numbers. For example in 2010, DHHS reported 800,000 people getting buprenorphine from office-based physicians, while only 27,456 were reported as receiving it through specialty treatment.

This is from a survey of patients being treated on one reference date in the year (the data most people refer to when claiming buprenorphine is underutilized) and doesn’t give a full picture of how many were treated throughout the year. I know of no way to estimate the full number that passed through these facilities in a year, but even the most generous assumptions would put the real number of specialty treatment clients at a fraction of the number of office-based clients.

Here are the original tables on specialty treatment clients:

Sources:

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS): 2016. Data on Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities. BHSIS Series S-93, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 17-5039. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2017.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS): 2019. Data on Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020.

New info: percentage of patients diagnosed with Opioid Use Disorder who received buprenorphine prescriptions

In 2019, the journal Addiction published an article in which researchers from Yale analyzed data on how many visits to doctor’s offices resulted in an Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) diagnosis and received buprenorphine prescriptions. The data came from a representative sample gathered in the 2006–15 National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys. They split the data into two 4-year periods. They found that in:

- 2006 to 2010 – 56.1% of patients receiving an OUD diagnosis were prescribed buprenorphine.

- 2011-2015 – 73.6% of patients receiving an OUD diagnosis were prescribed buprenorphine.

This shows that for the past 14 years, a majority of people receiving an OUD diagnosis have received buprenorphine.

Rhee, T. G., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2019). Buprenorphine prescribing for opioid use disorder in medical practices: Can office-based out-patient care address the opiate crisis in the United States? Addiction (Abingdon, England), 114(11), 1992–1999. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14733

New info: number of patients receiving buprenorphine, number of new buprenorphine prescription episodes, and length of treatment

The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) published a letter in January 2010 from researchers using a prescription database to give estimates on buprenorphine patients between 2009-2018

They found that in 2009 there were 351,904 people taking buprenorphine. The 2018 figure was 1,037,787. These differ significantly from what you’d expect having read the numbers in the first section above. For example, DHHS reported that by 2010 there were 800,000 patients receiving buprenorphine, but this source’s number for 2009 is 351,904. Furthermore, the 1,300,000 figure for 2014 cited by FDA researchers is significantly higher than the 2018 figure of just over a million reported here.

For 2017, they reported 457,166 new episodes of buprenorphine treatment, which they defined as new prescriptions to a patient who hasn’t filled a buprenorphine prescription in at least 6 months.

Of those new episodes, only 29.3% continued on buprenorphine treatment for 6 months or more. This number tracks well with most buprenorphine outcome studies I’ve seen. It also suggests a great amount of shuffle in annual buprenorphine patients, which pushes us further toward the conclusion that the majority of current buprenorphine patients currently fit the diagnosis for OUD.

Source:

Olfson, M., Zhang, V. (Shu), Schoenbaum, M., & King, M. (2020). Trends in Buprenorphine Treatment in the United States, 2009-2018. JAMA, 323(3), 276–277. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.18913

DEA number of grams of buprenorphine distributed annually suggest even higher patient numbers

A few years ago when I found most of the data in the first section, I compared it to the DEA’s figures on how much buprenorphine is distributed to pharmacies annually. The patient numbers from that section amounted to roughly half the number of grams distributed in corresponding years’ DEA ARCOS reports. From this, I estimated that in 2016 there were over 1.5 million patients on buprenorphine from office-based doctors and pharmacies. I give my estimate acknowledging that there are many factors that could effect this simple calculation, and it is by no means a perfect way to estimate patient numbers.

What’s the real number?

There’s not enough data to know exactly how many of the 2 million people with current OUD diagnoses are or have been treated with buprenorphine. But all the numbers above suggest that the real number is far higher than what is reflected by studies of specialty addiction treatment programs alone. There are many imitations to what I’ve reported here. For example we do not know what portion of patients receiving buprenorphine from pharmacies are using it only for pain relief purposes. [UPDATE: we now know that only 4.7% of buprenorphine prescriptions are for pain, which tells us the estimate should be fairly accurate – from Currie 2021 cited above]

We also don’t know what portion of patients receiving it would still fit the diagnosis for OUD. The NSDUH survey counts people as having OUD if they have fit the diagnostic criteria for it within the 12 months prior to the survey. That’s where the 2 million people with OUD number comes from. But once a person hasn’t fit the OUD diagnosis for 1 year or more, they will not be counted as having OUD. Long term (even lifelong) buprenorphine use is encouraged, so they may still be taking the medication for years after they’ve stabilized and no longer fit the diagnosis. On the other hand, there are cases who’ve been treated with it for years and still fit the diagnosis. These are all unknown quantities.

The JAMA data shows that new treatment episodes make up almost half of annual buprenorphine patients. It seems safe to assume that the vast majority of new patients have fit the diagnosis for OUD within that year (UPDATE: especially given that only 4.7% of prescriptions go to pain relief patients). Does that mean that the other half of patients are stabilized and recovered from their OUD problems though? Present diagnoses for long term buprenorphine users is a complete unknown. Furthermore, the counting of new cases in that letter leaves some questions. “New buprenorphine use episodes started on the date of a buprenorphine prescription fill after 180 days or more without a fill.” This possibly means that patients who start again within 6 months of their last prescription don’t get counted as a new case. But it doesn’t seem likely that they are stabilized “recovered” OUD patients.

I’ve been on a deep dive of this data trying to find answers for several years, and what I’ve found is that there are no solid easy answers. Whether or not we ever know the real number of buprenorphine patients with current OUD, it is much higher than suggested by those who cite specialty treatment statistics, and much higher than implied by statistics on the number of counties with buprenorphine waivered physicians, or percentages of waivered physicians throughout the country.

Buprenorphine treatment for OUD is much more widespread than it is represented to be in the media. And because of this, people with OUD are treated at a much higher rate than people with any other substance use disorders. The group of patients who receive it from office-based physicians is much larger than those who receive it from “specialty treatment” sources and should be considered in any discussion of whether or not buprenorphine is underutilized, and what it’s effects on the overdose crisis may or may not be. I hope this post provides useful fodder for those discussions.