The author of the iconic novel turned film about heroin addiction, Irvine Welsh, recently released a prequel to the famous story. He discussed his characters and some thoughts about addiction in a recent NPR interview. The difference between his own story and the standard narrative of why people use drugs is quite illuminating.

The author of the iconic novel turned film about heroin addiction, Irvine Welsh, recently released a prequel to the famous story. He discussed his characters and some thoughts about addiction in a recent NPR interview. The difference between his own story and the standard narrative of why people use drugs is quite illuminating.

Here he discusses why one of the characters got into drugs:

” … one of the main reasons I think is [the] symbiotic relationship with some of the other characters in the book, particularly Sick Boy’s character. I don’t think Renton or Sick Boy would have been junkies if they hadn’t met each other. It’s a kind of folly-of-youth thing that they have. They get introduced to sort of a small heroin subculture, and that becomes part of their life. And then what happens is this small subculture becomes a mass culture as the city becomes flooded with heroin, and everyone suddenly becomes into it, because it feeds off the kind of despair of mass unemployment and lack of social mobility in general. It’s a kind of no-brainer, because when there’s no employment and education and opportunities, it’s almost like drugs win by default. There is, literally, nothing else.”

I don’t disagree with this answer on its face – people do choose to follow what they think is their best available option for happiness – such is life. What I strive to show people though, personally, is that they don’t have to settle for a life that revolves around the cheap thrills of substance use, and that they’ll likely find far better options, should they choose to seek them out. I don’t happen to think that “there is, literally, nothing else” for people with substance use problems. With that statement and the comments about the despair of unemployment I think Welsh goes from explaining how some people may come to believe that excessive substance use is their best option for happiness- to excusing their limited perspective and reluctance to do better for themselves.

A lifestyle that revolves around heroin use is not a “no-brainer” for anyone – and when we say such things we’re really revealing an ugly, stifling judgment about people: that this is the best they can do – that their potential is small and inherently limited.

But there’s a disconnect between Welsh’s opinion of other people’s potential and his own potential, which comes across in his discussion of how he moved on from his own past with heroin use:

“For me … I wouldn’t say it was a very easy thing to do, but it was something that I just felt had run its course, and it wasn’t kind of offering me anything or showing me anything. It was just an inconvenience. And there was … nothing kind of driving it.’

What he’s saying is that he believed he could have and do better, and heroin use was standing in the way of greater happiness. The phenomenon of “addiction” running its course is nothing new, the epidemiological data actually show it to be the norm – people grow out, or “mature out” of these habits all the time (usually some time between the mid twenties to mid thirties – according to Gene Heyman in Addiction: A Disorder Of Choice, among other sources). But the idea that addictions run their course – that these are phases akin to what a teenager goes through when they ditch their teeny-bopper bands for classic rock or whatever they perceive to be more adult and “cool” as they mature – is under-recognized. When people come around to thinking that they have better options for happiness than running around getting high and drunk every day, they swiftly drop the habit – faster than an NSYNC cd hits the bottom of a trash can.

What’s sad, is that more people don’t fully realize that this is the case. If Welsh was in that world, he somehow chose to see beyond it, he peeked around the corner to see what might be next for him. Ostensibly, any of the “addicts” he writes about could do the same, it’s really just a matter of belief and effort to find more rewarding alternatives. Whether there’s a social program to coax people into finding better for themselves or not, the ability to see the opportunities is fully volitional – only the individual can choose to explore their options and believe themselves capable. When there are so many wonderful stories of people rising up from destitution and poverty, it’s sad that the possibilities get lost in discussions that only seem to provide excuses for stagnation.

He continues:

It’s not so much how you get off; I think it’s how you stay on is an important thing. I think there has to be kind of driving, compelling reasons to actually stay on drugs. And I think again, that comes down to sort of class and opportunity and poverty. … Anybody can get addicted to heroin, but if you don’t have any opportunities or anything going for you, it’s much harder to get off it.”

Human beings live with so much self-doubt – why saddle them with your own negative thinking and limiting judgments of their diminished potential? What’s good enough for Welsh should be good enough for any person with a destructive habit – there are no compelling reasons to use heroin once you choose to open your eyes to new possibilities of more rewarding choices for yourself. “Addiction” can run its course and cease to be an attractive option. It does so when people choose to expand and evaluate their options.

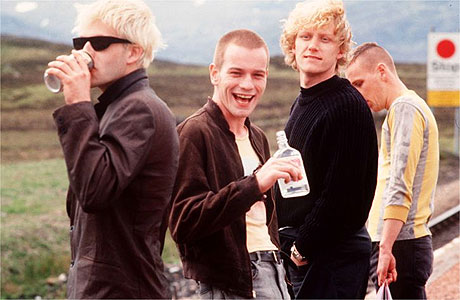

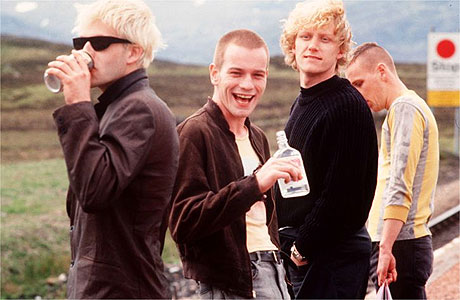

Here’s a link to the brilliant opening monologue to Trainspotting.

NOT true for me is this statement he makes, “And I think again, that comes down to sort of class and opportunity and poverty. … Anybody can get addicted to heroin, but if you don’t have any opportunities or anything going for you, it’s much harder to get off it.””

Not true for me. First, contrary to what Steven says is the norm about addiction, my vicodin addiction started after my mid 30’s and lasted 10 years. Second, contrary to what Welsh says, I had a graduate degree, was working, a perfect family, middle class, in excellent health, physically active. So I didn’t do it because I had no options. I didn’t do it because of my youth. ( In fact in my youth I spent 6 months freebasing and ended up in rehab).

My driving force to keep doing it was that I felt sick when I didn’t have it, and there weren’t compelling reasons to stop for many many years because I could afford the time and money to get it and nobody knew I was doing it.

So there, don’t think you have everybody all figured out!

Excellent article once again Steven. Two questions for Kelly, have you stopped using? And, why or why not? If a million people posted their personal experiences relating to substance use and substance use problems there would be a million different stories, but the fact remains that regardless of how you change your life, you first MUST believe that you can. Whether you believe it to be hard to quit, or easy to get; hard to stay stopped or easy to stay stopped — you will be right. Your belief is your reality.

I need to answer both your questions. So I totally agree with you! I had to believe I could stop. The reasons I stopped is that it took so much time and money to keep up the habit, I felt like I was a prisoner of my own making (disconnected from life), and my children were growing up and I needed to be more present. I felt guilty about spending my husband’s hard earned money on my habit. But it wasn’t until I heard about suboxone that I made the decision to quit! I was on suboxone for 6 months. I guess what I beat myself up about, is that I even did this, and for so long. It was my belief, that it was okay to do this, and my kinky contrarian personality that made me go forward. I still come on this site, looking for an answer, an answer perhaps that I may never find about why I did this. Heck, I left the illegal drugs behind long ago. I should have known better. I just didn’t have the knowledge of what I was getting into and where it might lead.

Hi Kelly,

I don’t know that you have anything to feel guilty about. There’s nothing inherently wrong with drug use. It doesn’t make you a bad person. We use drugs and alcohol for a simple reason – they provide a sliver of happiness, a bit of physical pleasure. The answer to why you did drugs was that you liked that feeling. The entire context of your life played into why you chose to keep doing it.

I speak of finding happier options, and it seems to me that you did that. And I should be careful to point out that when I say that, it doesn’t always mean that people take on new careers or whatever, and it doesn’t mean that thier present life sucks or isn’t rewarding. Sometimes it means that you gain the perspective that you’d like your present life minus the drugs more – and that then becomes your happier option.

At a certain point, you decided that being present with your kids, and having more time and money to do other things, would bring you greater happiness than continuing to use vicodin. That’s it. It is that simple. The recovery culture has taught you that it needs to be much more complex and dramatic than that – but it doesn’t.

When you say you didn’t have any compelling reasons to stop, I wonder why you feel guilty for using. You may be harboring unearned guilt on the basis of our culture’s view that a pattern of daily drug use for pleasure is a bad thing that bad people do. It is not.

I bring up the general pattern of what “usually” happens, in this article, because it supports the idea of “addiction” being a phase – but by no means does that phase have to take place at any particular age.

Also, I hope you know that my non-disease opinion isn’t necessarily anti-suboxone. I say this only because a lot of people seem to think that, and send me a lot of nasty emails, and I’m not sure why they think I hate them, but I don’t. I was once on methadone, so I know those drugs have a certain usefulness.

-Steven

Thank you so much for saying what you did. It brings tears to my eyes. I keep thinking I was such a bad person for what I did. I became emotionally less available to my children and I spent my husband’s money, and he’s such a good man. Mostly I feel bad about how I treated him, how I never had sex with him because I lost my drive for all those years.

I never thought you were pro or anti suboxone. I am not defensive on that issue at all, maybe because I don’t take it anymore. In fact suboxone is the only reason I thought I could quit. Without it, I’d still be taking vicodin (actually norcos).

Well, thank you again.

Michelle, yes I did quit using. Steven seems to focus on people who abused drugs in their youth while living an irresponsible lifestyle. I left that irresponsible cheap thrills stuff at age 21. Fast forward to my 10 yr vicodin addiction. I wanted to draw everyone’s attention to the many people who live normal productive lives and still have an addiction, usually hidden to the outside world, like the employer, or even their own family. That is my story. I met other people like me when I was in the 12 step rooms. We are never bad enough to get the press coverage about the pill addict or the alcoholic, or to have someone force us to stop. We work, we pay our bills, we raise our children, we volunteer in the community. One of my goals is to help that segment of people know they are not alone, there is help.