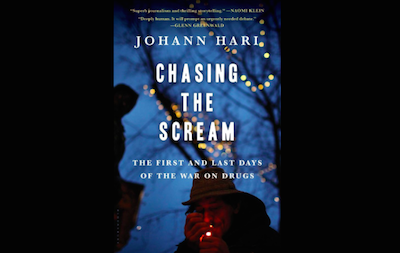

Journalist Johann Hari is peddling a new book on addiction, promising a fresh new take – and yet it may not be all that fresh – and it may not follow from the evidence he cites.

Hari is smacking down the disease model of addiction, specifically the one that depends on pharmacology. And for making this smackdown in front of a wide audience, he deserves some kudos. So, definitely, let’s give him kudos. But he follows this up by presenting what’s supposed to be a surprising account of the cause of addiction, and essentially gives us the well worn underlying causes/self-medication model of addiction.

This view has been around in a major way since at least 1985 (Fetting, 2012) and probably goes back further – rehabs have been “treating underlying causes” forever – they’ve been seeing substance users as maladjusted forever.

The model goes like this: people’s lives are crummy – they lack opportunity, they are alone and isolated, they have depression, anxiety, loneliness, et cetera, and they turn to heavy drug and alcohol use to soothe this distress – they “self-medicate.” Hari seems to focus more on the circumstances/environment side than most supporters of the underlying causes theory, but it works on the same basic principle. In Hari’s presentation, people are still seen as pushed into heavy substance use by something out of their control.

One of the major pieces of evidence that he cites (and again, Kudos for getting it in front of such a wide audience) is Lee Robins’s famous study of Vietnam vets who were ‘addicted’ to heroin in Vietnam. It’s a landmark study, because, as Hari correctly states, most of them stopped swiftly upon returning home. Moreover, those who jumped right into treatment programs ended up having ongoing problems, while those who didn’t get treatment did quite well in resolving their problems long term.

In an interview with Democracy Now though, Hari puts the environmental underlying causes spin on this evidence:

What happened? All the evidence is the vast majority come home and just stop, because if you’re taken out of a hellish, pestilential jungle, where you don’t want to be and you could be killed at any moment, and you go back to your nice life in Wichita, Kansas, with your friends and your family and a purpose in life, it’s the equivalent of being taken from the first cage to the second cage. You go back to your connections.

The bit about cages is in reference to Rat Park (another important study that the public should know about, so again, kudos!). The “first cage” is the one in which most drug experiments are done on rats – they live in isolation in a tiny little cage where their only form of pleasure is the option to push a button sending a jolt of cocaine or morphine directly into their brain, and not surprisingly, they keep pushing the button, often until death. The “second cage” was what the Rat Park researchers tried – give the rats a giant cage with toys and other rats and things to do, as well as access to morphine, and see if they choose the drug when they have other options. Importantly, it was shown that the rats didn’t go overboard with drug use in this case.

Thus we see Hari’s conclusion – the soldiers were like rats in the small cage when they were in Vietnam: they were stressed, isolated, miserable, and turned to the drug for comfort. However, their return home was like entering Rat Park – a land of support and love and opportunity, and thus they no longer needed to turn to heroin. This is the underlying causes/self-medication model all over again. Hari clearly demonstrates this view here, stating that the driver/cause of addiction “is isolation, pain and distress” as well as “suffering.” He continues “We have created a society where huge numbers of our fellow citizens can’t bear to be present in their lives and have to medicate themselves to get through the day with these drugs.”

The thing is, Lee Robins, the prolific researcher who headed the Vietnam studies, tackled Hari’s supposedly new and surprising interpretation of her findings back in 1993. In a lecture published in the journal Addiction, she defends her research from what she believes to be some wrong interpretations by others, writing:

The argument that addiction in Vietnam was a response to war stress, and therefore remitted on exit from the Vietnam war theatre, is still frequently cited as though it were self-evident, because it sounds so plausible. Yet accepting this argument is difficult in the face of the facts. Heroin was so readily available in Vietnam that more than 80% were offered it, and usually within the week following arrival. Those who became addicted had typically begun use early in their Vietnam tour, before they were exposed to combat. Further, the dose response curve that is such a powerful causal argument did not apply: those who saw more active combat were not more likely to use than veterans who saw less, once one took into account their pre-service histories… Those with pre-service antisocial behavior both used more drugs and saw more combat…

…the greater the variety of drugs used before entering service, the greater the likelihood that narcotics would be used in Vietnam.

(Robins, 1993)

Now, to be fair to Hari, Robins also makes some comments that might be interpreted as supporting his model, but I can’t get over how directly this hits at the underlying causes/self-medication interpretation of her findings – and the fact that she wrote this back in 1993. She’s saying that the users were more likely users beforehand, and that the stress of war didn’t have anything to do with it.

I’ll also say this is an issue I’ve thought about quite a bit. We’ve been tackling it at the Saint Jude Program, because we see troubled people who’ve been taught in addiction treatment programs to conceive of their substance use as being caused by their childhood trauma, unfortunate life circumstances, and emotional/psychological problems. As a result their problems seem to become compounded, they leave treatment worse off, feeling triggered to use whenever anything in life doesn’t go their way.

But beyond the sad cases who’ve learned to default to substance use until their lives are perfectly balanced (an impossible task for anyone), I see too many people whose situations really aren’t that bad by the measures that Johann Hari and other social crusaders would use as their benchmarks. Remember, Hari’s hypothesis is that the Vietnam vets heroin use was caused by their painful environment. They were…

taken out of a hellish, pestilential jungle, where you don’t want to be and you could be killed at any moment, and you go back to your nice life in Wichita, Kansas, with your friends and your family and a purpose in life

…and voila! They stopped heroin because of their new opportunity and environment. External conditions caused the addiction, and external conditions caused the recovery, and thus we just need to provide everyone with a bunch of love and support and opportunity and they’ll be caused to change too. If only it were that simple.

I see nice people with nice lives and beautiful families from Wichita Kansas or Toledo Ohio, or millionaires who live in posh apartments in NYC and the whole range of people who’ve got plenty of love, support, and social connection and opportunity surrounding them in their lives. Many of them are involved in their communities, families, churches, and other organizations. And yet these people feel as if they must drink and use drugs every day. They feel lost and out of control. The circumstantial model always seems to make sense when we’re entertaining our cliches of people with substance use problems – the down and out street user, the guy at the bus station begging for money to buy another hit of crack, the children of broken homes and poverty – but it doesn’t hold up when we look at the full spectrum of troubled substance users. It doesn’t explain the celebs, the millionaires, or the average soccer moms, the immigrants with strong supportive family ties, or the suburban kids from middle class families, or especially the ones from upper middle class families like I once was. It doesn’t explain why someone like myself, who had every opportunity to build a life for himself, chose the crash and burn path of heavy substance use instead. Thus it doesn’t show that an impoverished/rough environment is a necessary “cause” of addiction (never mind the fact that those who become “addicted” in these circumstances are still a minority within said circumstances). There are plenty of people living in the big cage – and yet they still live as “addicts.”

Mere observation disproves the notion that addiction is caused by poor circumstances, as we’ve seen above. But there’s also more addiction in wealthier countries, and less in poorer/third world countries (except for some outliers in the former Soviet states where extreme drinking is deeply embedded in the culture). There’s also a boatload of research that calls the self-medication model into question. For example, the most recent and largest epidemiological study on addiction and other psychological conditions, NESARC, found that:

No association was observed between mood and anxiety disorders and dependence remission for any of the substances assessed [nicotine, cannabis, alcohol, and cocaine]

Mood disorders included DSM-IV primary major depressive disorder (MDD), dysthymia and bipolar disorders. Anxiety disorders included DSM-IV primary panic disorder (with and without agoraphobia), social anxiety disorder, specific phobias and generalized anxiety disorder.(Lopez-Quintero et al., 2011)

If these psychological problems are supposed to cause addiction, how is it that people manage to end their addictions while still leaving with these problems?

I’m happy to see Hari getting some of this classic research and other factsout to a wide audience, but I don’t agree with his conclusions, nor do I find them new, surprising, et cetera. They’re all well worn retreaded theories – self-medication, underlying causes, environmental causes – they’ve been around forever. Hari says we need social recovery and that love and a bunch of other touchy feely stuff is the cure. We’ve tried that for 75 years – it’s called support groups. It’s now “family programs” at rehabs that bring the whole family in to learn how to be supportive in recovery. It’s now a year or more of aftercare and every sort of therapy imaginable. It’s the recovery culture instructing people on how to host sober holiday parties so that their loved one with a substance use problem will feel welcome, supported, and safe. I’m all for love, but this external control approach doesn’t work– you can’t “cause” people to become un-addicted.

It doesn’t work because regardless of whether you use the word “disease” or not, you expose people to all of the same pitfalls of the disease model when you teach them that addiction is a thing that happens to them. Whether a disease is causing you to use substances, or poor circumstances and lack of meaningful connections is causing you to use substances, these are both things outside of yourself.

Addiction is not a disease – and in fact it’s not really a thing at all. Addiction is really just a social construct though which society defines certain behavior as deviant and attempts to control it by convincing drug and alcohol users that they can’t control themselves and need to turn themselves over to the medical establishment to have their lives managed.

Take away the judgment of deviance, and what you see is a strong preference and a habit. If it was a preference for healthy cooking, we wouldn’t call it an addiction, yet it would operate on all the same principles. People develop strong preferences for drug and alcohol use the same way they cultivate and develop other interests in life – and if we’d stop misleading them into thinking that addiction happens to them, then maybe they’d thoroughly re-evaluate and change these preferences for the better. Or maybe them would keep doing lots of drugs and alcohol, and we could just accept that as their life choice instead of declaring them addicted and endlessly trying to make them conform to our view of how a life should be lived.

Here is the surprising news about the “cause” of addiction: there are no causes of addiction because addiction doesn’t exist. It is free human behavior. It is caused by the individual’s perspective on the relative benefits of drugs and alcohol as compared to their other perceived life options. Thus you can have all the options in the world, and yet if you don’t personally see them as providing a better life than heavy substance use, then they will lose to heavy substance use. You can dangle whatever you want in front of people, but it’s up to them to see that thing as attractive. Human behavior has reasons – not causes.

For a person to “self-medicate”, they must first see their drug of choice as a medication for their woes – they must reason their way to that choice. But the term “self-medicate” is inaccurate and misleading itself – drugs and alcohol do not pharmacologically medicate stress, trauma, depression, etc – and they certainly don’t pharmacologically catapult someone out of poverty or into loving relationships. They provide a physical sensation that can be interpreted as pleasurable. They are not so meaningful as our culture believes them to be – and the self-medication theorists only convince people to see drugs and alcohol as more and more meaningful when they credit them as answers to emotional suffering. They also convince troubled substance users to see themselves as weak and cornered into heavy substance use. This mindset disables them (I was once there).

If you don’t fully get what I’m saying here, you can check my article on “How to stop self-medicating” (hint – understand it’s not your medicine). Stress, anxiety, depression, and life’s curveballs can and will happen to everyone – and unfortunately these problems randomly hit some people more than others. While it’s great to try to reduce these problems, the answer isn’t to insure that they never occur again…. or else you’ll “relapse.” The answer is to mentally sever the mental connection between these problems and heavy substance use – dump the disabling beliefs!

If you don’t get why I’m saying the whole construct is disabling, then I think you may learn it by analogy. Listen to the story of the Batman on NPR’s This American Life. It’s about blindness, and how the blind are inadvertently hobbled by their helpers. I guarantee you’ll find it enlightening.

Citations:

Fetting, M. (2012). Perspectives on Addiction. Sage Publications. Retrieved from http://www.sagepub.com/books/Book235147?prodId=Book235147&ct_p=toc

Robins, L. N. (1993). The sixth Thomas James Okey Memorial Lecture. Vietnam veterans’ rapid recovery from heroin addiction: a fluke or normal expectation? Addiction (Abingdon, England), 88(8), 1041–1054.

Lopez-Quintero, C., Hasin, D. S., de los Cobos, J. P., Pines, A., Wang, S., Grant, B. F., & Blanco, C. (2011). Probability and predictors of remission from lifetime nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, or cocaine dependence: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 106(3), 657–669.

I agree that I’m not thrilled with Hari’s conclusions. Bruce Alexander is a ‘social utopianist’ and recommends more housing and support for addicts, despite all the great science he did. It doesn’t make sense. If addiction isn’t really a disease but just a reaction to torture then why give them more stuff? It’s not like they’re being tortured. But Hari seems to draw the same conclusions. Regardless, the fact that he brings to light so much original research that has been long since buried will start to turn the tide in how we think about it. I am very curious as to his attitude about AA, and whether he thinks it helps or hurts. Perhaps that will be his next book.

Two big endorsers of the book are committed 12-steppers Elton John and Russell Brand. I don’t know much about Elton’s views, but Russell Brand is clearly a dogmatic stepper. So ask yourself from there – how revolutionary can this book be?

Yes I saw the interview with Brand and was shocked he was supporting it. Maybe he doesn’t realize the implications of Hari’s work. But there is something even more important than ‘treating addiction’. And that is ending the drug war. I think Hari’s work is ambitious enough to make significant progress on that front. But otherwise I agree his ‘self-medication’ theory doesn’t make sense even though obviously some people do that. But in that case it’s not ‘addiction’. Typically they know why they drink even if they are not forthright in the reasons. They don’t lie and say, “I don’t know why I drink and I can’t stop no matter how hard I try.” That’s the 12 Step lie that people learn if they are unfortunate enough to get caught up in the cult. But that’s a different issue from the point of Hari’s book, which like I said is to end the drug war. “First things first.” 🙂

Hari talks about NA and AA here http://www.thefix.com/content/ending-drug-war-interview-johann-hari

“I think the bit that works with AA and NA is that it provides an alternative community where you can bond and connect. It’s a place where you can go and people care about you, they invest in you emotionally and you invest in them emotionally. You can become more like the rats in Rat Park and less like the rats in the first (isolated) cage. I think that is really important and I think it is the key as to why it works, when it does work. “

“Addiction is really just a social construct though which society defines certain behavior as deviant and attempts to control it by convincing drug and alcohol users that they can’t control themselves and need to turn themselves over to the medical establishment to have their lives managed.”

This is the most elegantly and baldly stated truth of what addiction is that I have ever seen. I also agree with your later statement that heavily using drugs and alcohol could be perceived as a lifestyle choice and not a sin or a misuse of life. Sadly, “addicts” (people who are labeled so) are the current scapegoat for our society, and for us to embrace this way of thinking we would have to, as a society, be able to function without a scapegoat…and I don’t see how we could change that fundamentally. People are always going to need a scapegoat (external dumping ground for sin and misery) in order to preserve their sanctimony and self-image, and since we have become too “advanced” to use an actual goat anymore, we will have to keep unconsciously projecting it onto certain subsections of humanity until we become more primitive again, I guess. Truly, I don’t know how we could change our outlook in such a way as to be able to embrace this way of perceiving “addiction”…do you? In any case, I’ve had to give up my license to be sanctimonious after my DUI so either way I am out of the game. Keep fighting the good fight, Steven, this is one of the most well-balanced alternative viewpoints of addiction on the entire Internet and I look forward to reading everything that you write. Godspeed.

Thanks T.,

I don’t know how to change society, but I know that each individual has some measure of “opting out” of this game available to them.

They can opt out by:

This is a really interesting article, thanks, getting at something that I also found didn’t sit well with me in Hari’s generally excellent book. I’m interested in hearing more about what you mean by ‘Human behavior has reasons – not causes.’ Especially, do you see this as a descriptive statement or a normative one, and how does it sit with the idea that a lot of human behaviour is pre-conscious?

‘Human behavior has reasons – not causes.’ – is a descriptive statement, based on a belief in free will.

The point is that our freely chosen thoughts cause our behavior – particularly, they are reasons when they take the form of “if I do X I will get Z” – where X is a particular action, and Z is the currently preferred result.

If I reasoned that dish soap would cure all my emotional pain, then I would drink dish soap whenever I had emotional pain. In this case, would you say that my emotional pain caused me to drink dish soap, or would you say that my belief that “dish soap cures emotional pain” was the cause?

I think my belief (reason) would be the cause. There are literally billions of human beings who don’t drink dish soap when they feel emotional pain, so how could we ever conclude that emotional pain causes dish soap drinking? It defies logic. It defies the meaning of the term “cause” which is a strong word. The cause is my reasoning, which resides in my mind, and which only I can change with the insight “dish soap doesn’t actually cure my emotional pain.”

A focus on the pain itself is a step removed from the real cause (my reason). Yet, many people would go a further step away by focusing the circumstances in my life that are connected to my emotional pain (e.g. a divorce, or loss of some kind, or memories of childhood abuse). This again is missing the point. Plenty of people have these poor circumstances and far worse, and yet they don’t respond to them by drinking dish soap. Only the people who believe dish soap cures emotional pain and is a good response to these circumstances will actually drink dish soap in response to them. Therefore, it is that belief (in the form of a reason) that is the true “cause.”

I’m not sure what you mean by pre-conscious behavior. I can only guess that you mean some form of determinism that would perhaps refer to Libet’s experiments as proof that we decide to take an action before we think of it. If that’s what it is, we can talk about it, and I can give put out some criticism of the meaning of the Libet experiments, and non-free-will views of humanity. And, my view of human behavior having reasons rather than causes would definitely not fit with it. Either way, I’m interested in what you mean by pre-conscious human behavior.

Thanks,

Steven

Hi Steven

a simple example of pre-conscious behaviour would be yawning. And I’m thinking more of the work of behaviour scientists like Daniel Kahneman, which suggests that much more behaviour than we think is pre-conscious. My reading of behaviour science is that multiple factors influence behaviour and reasoning is often post-hoc. In my own work I’ve found the ‘COM-B’ model to be a useful model of behaviour. It understands behaviour in relation to capability, opportunity and motivation. Motivation is understood as having reflective and automatic components and reasoning fits within the former. The PRIME model of addictive behaviour is also useful, and can be combined with COM-B.

To me, the fact that you base the idea of reasoned behaviour on a belief in free will suggests it’s more a normative than a descriptive statement – and in those terms, I’m right there with you: I also value reasoned choice. It’s an important to how we understand ourselves as human, and it’s also a useful strategy for breaking with habitual behaviours.

I found relief with from trauma by using alcohol in my teen years. I never developed good coping skills until recently. I don’t consider addiction a disease, but I agree that trauma and environment can contribute to substance abuse. T o quote your article,

“Hari says we need social recovery and that love and touchy feely stuff is the cure. We’ve tried that for 75 years-it’s called support groups”. I believe that the type of support group we have used is a big part of the problem. Twelve Step programs are the go-to groups, and from my personal experience, AA contributes to depression, low self-esteem, anxiety, and fear. AA certainly perpetuates “disabling beliefs”.

I think more supportive support groups such as SMART and Women for Sobriety can help people. They have been around for decades, but 12 Steps have the market cornered. That’s a social problem I’d like to help change!

Thank you! I too am slightly annoyed by the amount of attention Hari is getting. This is old news, and far from monumental.

Just another opinion of a non-allergic person thinking their reaction to said allergen can be replicated in all others. Denying peanut allergy exists because you don’t understand others’ reactions to peanuts…. Allergic types should man-up, right? Sorry but willpower doesn’t work for true allergic types.

“…drug and alcohol…”

NO. it’s alcohol and other drugs…

Do not ever dismiss alcohol as something other/lesser than a drug.